As you know by now, Derek Jeter returned to the Yankees this weekend for the paltry sum of somewhere around $17 million per season for three seasons, with a possible 4th year option. It’s hardly worth Jeter’s time, as the single greatest player in the history of any sport ever, to even consider getting out of bed for $17 mil, but if he can will himself and his teammates to win surely he can motivate himself to play even when he is so drastically undervalued as to be playing for virtually nothing.

As all news, all the time, should be Jeter-centric, The Common Man is offering two companion pieces today and Tuesday, on the 40 greatest Yankees of all time and the 40 greatest SS. Feel free to argue in the comments section. That’s, obviously, what the comments section is for. Without further ado, the 40 greatest Yankees ever as determined by Baseball Reference.com’s Wins Above Replacement (WAR) as a Yankee.*

*Note, in certain cases, however, TCM has taken the liberty of adjusting certain rankings when a player missed time due to actual war (as opposed to WAR), and some slight adjustments based on both service time, peak value, and general glory as determined by World Series performance. TCM will try to make these cases apparent. Also, all statistics include only the time the player served as a Yankee.

40) Wally Pipp (.282/.343/.414, 106 OPS+, 121 3Bs, 80 HR, 27.9 WAR)

Geez, can’t a fella take one day off? Believe it or not, the Yankees’ predecessor to Lou Gehrig was one of the most durable players in baseball. From 1920-1024, he missed a grand total of 12 games. And in 1925, he had played each of the Yankees first 42 games when he supposedly begged out with a headache. Pipp would later say, “I took the two most expensive aspirins in history.”

Contemporary papers, however, give a different account. Billy Evans, of the Palm Beach Post, wrote on June 11 (10 days later),

“Managers are superstitious. When a club is going bad they will try most any combination in an effort to win…. On the bench were such star performers as Wally Pipp, Aaron Ward, Everett Scott, Whitey Witt, Wally Schang, and all the veteran pitching stars. While most of these veterans will shortly be restored to the lineup…the shift makes it apparent that the Yankees are to be rebuilt.”On the 16th, Dick Gibson of The Morning Leader wrote this damning report,

“Huggins set out the other day to discipline a few of the stars who had been playing indifferent ball. He benched Wally Pipp and Aaron Ward, and sent Benbough behind the bat in the place of veterans Schang and O’Neill. These and others had openly challenged Huggins’ right to rule and the ‘mite manager’ lost no time in showing who was boss. Not only did he discipline the mutineers but he got results—the re-organized club coming through with wins over Washington, Philadelphia, and St. Louis. Now it’s likely that a half-dozen of the conceited veterans will be displaced by ambitious youngsters between now and the start of the 1926 season. Professional athletes are entitled to every consideration as long as they are honestly giving their best, but hwen they loaf and break training ules they should and must be disciplined.”Anyway, Pipp never started another game for the Yankees, as Gehrig pounded out three hits, including a double, and scored a run. Later that year, Pipp was hospitalized for a concussion after being hit in the head with a ball during batting practice (ironic, given the recent suggestions about the reasons for Lou Gehrig’s demise). He was sold to Cincinnati that winter, where he’d have one more good season before fading into baseball history.

39) Roger Maris (.265/.356/.515, 140 OPS+, 275 HR, 27.9 WAR)

Maris only lasted seven seasons in New York, and if it were up to him, he probably would have preferred less. Roger won back-to-back MVP awards at the start of his Yankees career, including his legendary 61-homer campaign in 1961. Never popular with the media, Maris was greatly maligned when his production began to head south, largely because of a stingier run-scoring environment and various injuries that took their toll on him. Maris played most of 1965 with a broken bone in his wrist that went undiagnosed. The press and Yankee brass figured he was loafing and a malcontent and bashed him at every opportunity. In 1967, he was finally traded to the Cardinals, where he had two productive years and reached the World Series both times.

38) Bobby Murcer (.278/.349/.453, 129 OPS+, 175 homers, 27.1 WAR)

Poor Bobby Murcer. A founding member of the Hall of Very Good, Murcer had a terrific career that included 13 years as a Yankee. He was a productive player for most of that time, and was exceptional in 1971 and 1972. Alas, because he was a converted SS from Oklahoma who was playing CF for the Yankees, he got dubbed “the next Mickey Mantle.” But his performance could never measure up to the immortal Mick, and his arrival coincided with a stretch of mediocre ball from the Bronx Bombers, and Murcer never truly was accepted by Yankee fans. Murcer got traded by the Yankees to the Giants prior to the 1976 season, and missed the iconic run from 1976-1978. He came back in ’79 and was a part-time player until he retired after 1983. Amazingly, this Yankee great had just 14 career postseason plate appearances, and just one hit. Murcer missed two years from 1967-1968 for military service at the start of his major league career, but it’s unclear how productive he would have been as a 21 and 22 year old.

Here’s Bobby on a 1971 episode of What’s My Line?

37) Elston Howard (.279/.324/.436, 108 OPS+, 161 HR, 28.7 WAR)

It’s really gratifying to see Ellie Howard on this list, The Common Man won’t lie. Howard spent 3 years in the Negro Leagues, playing for Buck O’Neil’s Kansas City Monarchs until the Yankees finally signed him in 1950. Military service in the Korean War took him away from the game in ’51 and ’52, but he forced himself into the team’s plans with excellent performances in both the American Association and the International League in ’53 and ’54. In 1955, he broke camp with the Yankees, but Casey Stengel wasn’t sure what to do with him, given he already had one of the best catchers of all time in the lineup, “I don’t know right now where I’ll play him. But he’s got to be in there some place, even if he just pinch hits. He is a wonderful catcher. I think he’s best at that. He throws good and he handels the pitchers well.”

Howard spent most of his rookie year coming off the bench or playing LF, and only started behind the plate in four games. Slowly, though, he began supplanting Berra behind the dish until eventually Yogi was the one pushed out into LF in 1960 and 1961. Despite his late start, Howard made nine All Star teams and was the MVP of the 1963 season, when he hit 28 homers. Howard would rank much higher if he hadn’t had to spend so much time out in LF and at 1B, where the bar for offensive production is so much higher. Virtually everyone who met Howard spoke of his poise, dignity, and decency.

36) Herb Pennock (162-90, 3.54 ERA, 114 ERA+, 29.2 WAR)

Herbert Pennock is one of the more unfortunate inclusions in the Hall of Fame. He was a fine pitcher for many many years, and supposedly possessed one of the greatest curveballs of all time, but really only had four HOF-caliber seasons. He’s probably in the Hall primarily for playing on the 1927 Yankees. In the Neyer/James Guide to Pitchers, Rob and Bill quote a 1930 Baseball Magazine article in which Pennock describes the secret of his success as “a thin wrist.” The article goes on to note, “Pennock’s arm is as thin as a high school girl’s from shoulder to wrist. His biceps is conspicuous by its absence. In fact, his arm appears so frail that it would impress the observer as quite unsuited to the grilling labor of the hurling mound.”

35) Roger Peckinpaugh (.257/.334/.342, 93 OPS+)

In 1912, the Cleveland Indians featured two 21 year old shortstops, Ray Chapman and Roger Peckinpaugh. In 258 plate appearances, Peckinpaugh hit .212/.262/.250. Chapman, meanwhile, hit .312/.375/.422 in 132 chances and won the job outright. The next year, in an incredibly lopsided deal, Peckinpaugh was dealt to the New York Yankees for two players who totaled 90 plate appearances for the Indians between them. Roger, meanwhile, became a star in New York and a mainstay in the Yankee infield for the next nine years. Chapman grew into stardom as well, playing nine excellent seasons for Cleveland. On August 16, 1920, Chapman was struck by a Carl Mays fastball in the temple in New York. The Yankees SS that day? Roger Peckinpaugh. Peckinpaugh and Chapman were both 5'10". Did his terrible performance in 1912 save Roger Peckinpaugh's life? There but for the grace of God…

34) Mike Mussina (123-72, 3.88 ERA, 115 ERA+)

Despite the rise in his ERA, Mussina may have actually been a better pitcher in New York than in Baltimore. His K/9 went up, his BB/9 dropped, and his HR/9 virtually held steady. What changed? Probably the defense behind him. With the Orioles, Mussina posted some pretty terrific BABIP numbers, especially early in his career. From 1991-1995, for instance, Mussina’s total BABIP was .264. As his teams aged around him, however, the total spiked. From 2001-2008, the total was.307. If Mussina doesn’t end up making the Hall of Fame, he can thank outfields that featured Johnny Damon, Melky Cabrera, Bobby Abreu, Gary Sheffield, Bernie Williams, Hideki Matsui, Chuck Knoblauch, Paul O’Neill, and Rondell White.

33) Waite Hoyt (157-98, 3.48 ERA, 115 ERA+, 31.7 WAR)

Hoyt is another Hall of Famer created by the ’27 Yankees. And Hoyt was really good that year. But it’s really his only HOF caliber season. But winning 22 games for the supposed best team of all time and getting the “ace” label will stick with a fella. Hoyt pitched for 21 years in the big leagues, 10 of which were for the Yankees. In those other 11 seasons, Hoyt had a winning record just twice, both times as a swingman for the Pirates in 1934 and 1936. In the offseason, Hoyt was a successful funeral home director and vaudeville showman. Because that totally makes sense.

32) Spud Chandler (109-43, 2.84 ERA, 132 ERA+, 11 seasons, 26.0 WAR)

Chandler was really only a terrific pitcher in two and two-thirds season. He was a star college football player who signed a professional baseball contract far later than most prospects, at 24 years old. The Yankees had stellar pitching and a deep minor league system, and Chander’s minor league performance was inconsistent at best. He spent 5 more years down on the farm, and didn’t debut in the majors until he was 29. Chandler battled injuries for much of his early career, including a broken leg in 1939 that left him only able to throw 19 innings. By 1942, however, Chandler was establishing himself as one of the league’s better hurlers. In 1943, at age 35, he went 20-4 with a 1.64 ERA with 20 complete games, and was named the AL MVP. He was incredibly tough in the World Series that year, throwing two complete game victories against the St. Louis Cardinals while allowing just a single run. After pitching one game in 1944, Chandler was drafted into World War II, but spent most of almost two full seasons in Georgia. In 1946, at 38, he was 20-8 with a 2.10 ERA and another 20 complete games. Bone spurs apparently cut Chandler’s final season, in 1947, short, and he never pitched in the majors again. Chandler has the highest winning percentage of any modern pitcher with more than 100 decisions. He gets bumped up a couple spots here for losing almost two full years to the war.

31) Rickey Henderson (.288/.395/.455, 135 OPS+, 78 homers, 326 SB)

It’s remarkable that Rickey ranks as highly as he does on this list, given that he only played five years in pinstripes. No one else made the list with fewer than seven seasons. He made it primarily because of his remarkable 1985 season, in which he was absolutely jobbed out of the MVP award by his teammate, Don Mattingly. Rickey hit .314/.419/.516 with 24 homers and 80 SB against 10 CS, and scored 146 runs, while also driving in 72. His OPS+ was 157. But, of course, writers valued (and still value) guys who drive in runs, rather than those that create them on their own, and so Mattingly got the crown despite driving in one fewer run than Henderson scored. Henderson also started 137 games in CF that year (his first extended exposure to the position), and by all the metrics played it exceptionally well. By the way, The Common Man loves Rickey Henderson.

30) Bob Shawkey (168-141, 3.12 ERA, 117 ERA+, 37.6 WAR)

Bob Shawkey was purchased by the Yankees off of Connie Mack as the A’s boss was dismantling his team yet again. Shawkey was probably a better pitcher than Hoyt and maybe Pennock, but had the misfortune to be almost used up by the time 1927 rolled round. In between, he won 20 games four times, including 1919 when he won five games in six days,

After Miller Huggins died, the Yankees tracked Shawkey down to the north woods of Canada to offer him the manager’s job that Shawkey’s former teammate Babe Ruth thought should be his.“Any pitcher who can go out and win one game in four thinks he is doing pretty well, but here is Bob Shawkey making all such look like rank losers. The veteran member of the New York Yankees pitching staff, who has been doing noble work both on his own account and as a relief man, achieved the remarkable distinction recently of being credited with winning five games in six days. Shawkey started his record in the series in Washington, where he was called on as a relief in three games. In one he pitched one inning, in another three innings and in the other two. The score was such that in each he got credit for the victory. From Washington the Yankees went to Philadelphia. There Shawkey worked a full game and won. The next day he was called on as relief man and the Yanks won another game, with Shawkey given credit….Bob is pitching good ball when called on and critics who have been blinded by the glare of younger twirlers are beginning to give him due credit.”

29) Mel Stottlemyre (164-139, 2.97 ERA, 112 ERA+, 37.9 WAR)

Pity Mel Stottlemyre, a very good pitcher who debuted just as the Yankees were falling into the clutches of CBS ownership. The Yankees were 3.5 back of the Orioles and 2.5 behind the White Sox when Mel was called up to start his first game on August 12, against Chicago. He pitched a complete game and gave up just two earned runs. He beat the division leading O’s four days later, pitching 8.2 innings of one-run ball, and followed that with a shutout against the Red Sox. In September, he reeled off a five game winning streak to help the Yankees get control of the American League, and finished the season 9-3 with a 2.06 ERA in 12 starts. He started three World Series games that October, including Game 7 on two days rest, and went 1-1 with a 3.15 ERA. But the Yankees lost to the Cardinals, and Stottlemyre never got another shot at the postseason. Mel pitched a lot of innings at a pretty young age, so it shouldn’t be all that surprising that his shoulder gave out in 1974. He had reconstructive surgery, and attempted a comeback in ’75, but was released before Spring Training ended. He never pitched in the majors or minors again.

28) Andy Pettitte (203-112, 3.98 ERA, 115 ERA+, 39.6 WAR)

Some of the most fanatic of Yankee fans have taken up a Hall of Fame case for Andy Pettitte based on his 240 wins and 19 postseason victories. Quite simply, this would be a mistake. Pettitte has been a good pitcher for a long time, but was really only dominant in one season (1997). Pettitte’s postseason totals are bloated by all the extra postseason games he’s gotten into because of the division series and championship series. His World Series records (5-4, 4.06) is nothing to really write home about. Let’s not get crazy anointing St. Andy just yet.

27) Don Mattingly (.307/.358/.471, 127 OPS+, 222 homers, 1099 RBI)

This is going to infuriate some of you, especially Bill James who famously wrote that Mattingly was “100% ballplayer, 0% bullshit”. But Mattingly simply was not an outstanding player after 1989, and no amount of revisionist history can get you past that. Yes, he was hurt, but staying healthy is a skill. There’s a reason that Doc Gooden is not going to be in the Hall of Fame, after all. Indeed, Mattingly was never as good as his supporters suggest he was, never posting a WAR above 6.9 in his career. Donnie Baseball may have been a good player, and a gamer. But how he epitomized baseball to so many New Yorkers who had the pleasure of watching Willie Randolph and Rickey Henderson at the same time is baffling to The Common Man. Must have been the mustache.

The just passed Gil McDougald, on the other hand, is criminally underappreciated. McDougald played 2B, 3B, and SS for ten years for the Yankes, providing excellent glovework at each stop and solid on-base skills. McDougald famously quit the game in 1960, after just ten seasons and at 32 years old. Presumably he still had some good baseball in front of him, but just didn’t enjoy the game anymore, particularly after his line drive up the middle was so devastating to Herb Score, “I just got tired of the travel, and the attitude of the baseball people. I started at $5,000 a year with the Yankees, and then was making $37,500 at the end. But they acted like they owned you and that they were giving you the moon and stars.” (h/t to Pinstripe Alley) If you squing, McDougald looks a lot like a young James Coburn.

25) Graig Nettles (.253/.329/.433, 114 OPS+, 250 HR, 40.6 WAR)

Speaking of underappreciated, Nettles was a tremendous 3B for the Bombers for 11 years. Between the low-output offensive era in which he played and slotting his prime between the careers of Brooks Robinson and Mike Schmidt, which meant his defense got short shrift, it’s a wonder anyone noticed him. After the death of Thurman Munson, Nettles was made team captain, and retained the title until after 1983. At that point, Nettles was escorted out of town when it became apparent he was publishing a tell-all memoir of his time with the Yankees, Balls, that was critical of George Steinbrenner. The book was not well received, called “a humorless ill-tempered diatribe against the Yankees’ owner… periodically interrupted by contemptuous comments about sportswriters in general.”

24) Alex Rodriguez (.296/.393/.559, 147 OPS+, 268 homers, 40.9 WAR)

Never heard of him.

23) Charlie Keller (.286/.410/.518, 152 OPS+, 184 homers, 42.4 WAR)

King Kong Keller was short, hairy and absolutely hated his nickname. But he was an amazingly powerful player built sort of like Matt Stairs. Keller absolutely had Hall of Fame ability, and almost certainly would have made it if he had not ruptured a disc in his back just prior to the 1947 season. An unattributed feature by the United Press on Keller from the 1947 World Series paints a sad picture of this great player, and is a great reminder of how amazing sports writers used to be (Posnanski and Gammons excepted):

“He huddled there in the gloomy shadows of the players’ pit and there was a fear and an uncertainty in those valiant eyes. Nervously his twitching fingers clutched the still-stained wrists, dyed a deep brown last Spring under the sun. Those were the days when Charley, the fearless kid from Frederick (MD), was joining the Yankee immortals as a terrible man to face when runners danced on the basepaths. Now all that was gone. So, too, were his hopes for the future. ‘Oh God,’ Charley said, and there wasn’t blasphemy in his voice….

Between the vertebrae are tiny little fluid-filled washers. In Charley one of them broke—and the mighty machine destined for baseball greatness became a pathetically weak mortal whose legs faltered and flagged though the spirit continued to flame. For a long while, Keller kept his hopes alive, through an operation, as his Yankees drove to the American League pennant.

But yesterday, in the gloom of the dugout, King Kong Charley admitted that he might be near the end of the road. ‘I don’t know, I won’t know, probably, until next Spring, whether I’ll ever be able to play again.’ The eyes were haunted and tear-filled as he said it. And while you loved the guy for what he is and what, with continued health he could have been, you wanted to get away from him. For it’s hard to believe that at 31 a man’s best years are behind him.”

22) Joe Gordon (.271/.358/.467, 120 OPS+, 153 HR, 36.3 WAR)

Joe Gordon had the impossible task of trying to follow up the immortal Tony Lazzeri at the keystone for the Bombers, but the Yanks were sure he was ready after he hit 26 homers at AA Newark in 1937. He was a great player from the moment he stepped on the field in 1938 until 1943, and exceptional when he won the MVP in 1942. “Flash” missed two absolutely prime seasons in 1944 and 1945 to World War II, and when he came back he needed to play his way back into shape. The Yankees had Stuffy Stirnweiss and needed pitching, so they dealt him to Cleveland for Allie Reynolds after 1946. The trade worked well for both clubs, but after a relatively poor showing in 1950, Gordon asked for his release to become player-manager for the Sacramento Solons of the Pacific Coast League. In 568 PAs against AAA pitching, Gordon had hit .299/.399/.627 with 43 homers and 136 RBI for a team that lost 92 games. Still, Gordon was viewed as a strong managerial prospect and had good success with the 1959 Indians. In 1960, he and Detroit Tigers manager Jimmie Dykes were essentially traded for each other, though neither club got any better.

About Jimmie Foxx: “He had muscles in his hair.”

Of Charlie “King Kong” Keller: “He wasn’t signed. He was trapped.”

To what did he attribute his success: “To clean living and a fast outfield.”

What happened after hitting a double and being picked off second, “How should I know, I’ve never been there before.”

After his triple-bypass operation in 1979: “That’s the first triple I ever had.”

And on his induction to the Hall of Fame, in a moment of apparent supreme self-awareness whether he meant it to be or not: “I want to thank all my teammates who scored so many runs and Joe DiMaggio, who ran down so many of my mistakes.”

20) Thurman Munson (.292/.346/.410, 116 OPS+, 113 homers, 43.4 WAR)

Would Thurman Munson have been a Hall of Famer if he hadn’t died in a plane crash in August of 1979? It’s hard to believe at first glance. Munson was already 32 and had caught more than 11,000 Major League innings to that point. That’s a lot of knee bends. And his offensive performance had definitely diminished over the last two seasons with the Yankees, especially his power. However, his defensive performance was still excellent, indeed it seems to have improved over his MVP year of 1976. And for a catcher, his offense was still more than acceptable. It’s likely that Munson would have gotten at least one to two more years of solid production out of him, and a couple more years in a job-sharing arrangement. He still likely would have played in both the 1980 playoffs and the 1981 World Series. That would have gotten him near 2,000 hits, but his rate stats would have decreased somewhat (in particular that slugging percentage). He was already better than Rick Ferrell and Ray Schalk, and may have been better than Ernie Lombardi and Roger Bresnahan. Gabby Hartnett and Bill Dickey also may have been in range. So the answer is…um…maybe.

19) Ron Guidry (170-91, 3.29 ERA, 119 ERA+, 44.4 WAR)

Was Gator the best pitcher in baseball from during his era? It’s close. Using BaseballReference.com’s totally awesome Play Index, The Common Man looked at the best pitchers in the AL with more than 2000 IP from 1975-1990. Of those pitchers, Guidry’s 119 ERA+ comes in third behind (and Bill’s going to love this), Dave Stieb and Jim Palmer. Palmer, however, pitched 300 fewer innings and consistently underperformed his FIP by a significant amount, which suggests something wrong with the metric or something right with the defense behind him (Guidry hovered right around his FIP). Stieb, however, pitched almost 300 more innings that Guidry, and maintained a good FIP (though it was a half run higher). It’s probably about a toss-up, which suggests that Guidry actually has a pretty good Jack Morris-esque Hall of Fame case.

18) Roy White (.271/.360/.404, 121 OPS+, 160 homers, 44.5 WAR)

Frankly, TCM isn’t sure what to say about Roy White, a good player with one exceptional skill, his eye. And that eye kept him in The Bronx for 15 years almost exclusively as the Yankees leftfielder. He was an ok fielder, had a little speed, line drive power. But he had the singular ability to draw 70-100 walks a year in his sleep. White was shifted into a reserve role in 1979, and it didn’t take. Rather than sit on the bench, he signed as a free agent with the Yumiuri Giants, one of the first prominent American players to go to Japan, where he played for three seasons with Saduharu Oh.

17) Earle Combs (.325/.397/.462, 125 OPS+, 44.7 WAR)

Yes, Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig made the Yankees of the 1920s and ’30s go. They were dynamic and powerful sluggers who, as Bill James suggests in his New Historical Baseball Abstract, were worth 2 superstars each. But Ruth, in particular, needed someone to knock in on occasion, and Combs readily provided. His .397 OBP was excellent, even for a high offense era, and his defense was apparently impeccable in spite of a weak throwing arm. Combs’ career was cut short after injuries prematurely ended his 1934 and 1935 seasons. In ’34, Harland Clift was at bat on July 24 when he hit a long fly to left field,

“Combs, running at top speed, crashed into the concrete front of the bleachers after making the catch…. The unconscious player was hurried from the field, while Dr. Leo Bartels, watching the game as a spectator, examined the veteran in the Yankee clubhouse….Combs was found to be suffering from a fractured skull and a broken collarbone, and was placed on the list of critical cases at St. John’s Hospital.”Combs remained in the hospital (and stuck in St. Louis) for more than two months. He came back in 1935, with some success (though his ability to hit for extra bases was way down). In August, Combs ran in to get a short fly ball off the bat of Jimmy Dykes, and crashed into Red Rolfe, completely tearing ligaments in his throwing shoulder. He was done for the year, and took a job as a coach the next year with the Bombers. Given his replacement in 1936 was Joe DiMaggio, Yankee fans didn’t miss his production much.

Tommy Henrich originally signed with the Cleveland Indians in 1934 and quickly established himself as a prospect. He hit a veritable ton everywhere he went (his lowest average was .325, and his lowest slugging percentage .518 over the course of three seasons. Cleveland had three good outfielders, and a strong 1B but didn’t want to lose the young prospect. To keep other clubs from drafting him out of the minors, they shifted his contract to its affiliate, Milwaukee in the American Association, in an effort to shield him from a minor league draft. Henrich blew the whistle to Commssioner Landis in an effort to

“find out whether Milwaukee really owned me or Cleveland still had control over me…. Half the time I hear that I belong to Milwaukee and half the time I hear that I belong to Cleveland. If I belong to Milwaukee, I’d like to know how they got me when major league clubs tried to make deals for me and couldn’t. In other words, I’ve been sold twice to higher leagues at Cleveland’s direction, yet I never even saw a Cleveland contract. If I belong to Cleveland, I’d like to know why I never signed a Cleveland contract. It is all very confusing to me. I’d like to know once and for all who I really belong to.”Landis investigated and found that

“he has been ‘covered up’ for the benefit of the Cleveland club and that his transfer from New Orleans to Milwaukee was directed by the Cleveland club and prevented his advancement to a major league club under the selection clause. Because of the violation of the player’s rights under his contract and the major-minor rules, he is hereby declared a free agent.”The Yankees bested six other clubs to get the young outfielder, acquiring him for an undisclosed sum that was probably in excess of $20,000 (given that’s what Giants manager Bill Terry had publicly offered for him). At his best, Tommy Henrich was a Hall of Fame quality player, and gave the Yankees 11 excellent seasons. He missed three years in the Coast Guard for World War II and retired after back and knee injuries made it too painful to keep playing. With those three years back, he might be in Cooperstown today.

15) Jorge Posada (.275/.377/.479, 123 OPS+, 261 homers, 46.0 WAR)

Jorge Posada is a rare breed. Most catchers decline dramatically after turning 32 or so. Among catchers older than 32 who played at least 500 games, Posada is second all time in OPS+, behind only Gabby Hartnett. Hartnett never played more than 100 games from age 37-40, and Jorge’s probably at that stage now. His last 100 game season behind the dish was 2009, and he started only 88 of those contests. With the rise of Cervelli and Montero, he’s bound to get less time now that he’s going to be 39. A great player in the twilight of his career who, by rights, should make the Hall of Fame someday.

14) Tony Lazzeri (.293/.379/.467, 120 OPS+, 169 homers, 46.6 WAR)

Tony Lazzeri caught the Yankees’ eye as a 21 year old when he hit .355 and 60 homers in the Pacific Coast League in 1925. A couple of important caveats though. First, Paul Waner hit .301 that year, Lefty O’Doul hit .375, and someone named Frank Brower hit .362. It was a high offense league. Second, Lazzeri played in Salt Lake City, where the weather was dry and the air was thin, which contributed to a vintage Coors Field atmosphere. Third, Lazzeri played in 197 games that year out of a possible 199 on Salt Lake’s schedule. In a 154 game environment, that’s about a 48-49 homer pace. It’s still incredibly impressive, of course, just not quite as historic as it seemed. In the Majors, he never hit more than 18 in a season. Lazzeri started playing professionally at 18, and finished when he was 39. That’s 22 years in organized ball, more than half of his life. He died young, at 42, after suffering either a heart attack or epileptic seizure, and fell down a set of stairs.

13) Bernie Williams (.297/.381/.477, 125 OPS+, 287 homers, 449 doubles, 47.3 WAR)

Beloved by all, but probably not Hall of Fame bound even though he’s much (much) better than several outfielders already there. His raw numbers just aren’t pretty enough for most writers. He didn’t top 2500 hits, didn’t hit 300 homers, and didn’t top a .300 average. But he had a terrifically well rounded game punctuated by excellent plate discipline. Bernie will probably fade into the background as history marches on, and be terribly underappreciated by future generations of baseball fans.

12) Willie Randolph (.275/.374/.357, 105 OPS+, 49.8 WAR)

Go ahead, Mattingly fans, get angry. Hate on this. Willie Randolph is one of the most underappreciated players in baseball history. There, it’s been said. He did things that don’t show up in traditional analysis. For one thing, he was very patient. He was also a plus defender at 2B. Looking at his whole career, Willie should probably be in the Hall of Fame.

The Yankees got him from the Pirates after 1975. The Bucs were wedded to 24 year old gloveman Rennie Stennett at the keystone, and desperately wanted Yankees’ righty Doc Medich, a 26 year old workhorse. The Yankees extracted Randolph, Dock Ellis, and Ken Brett for him. Ellis cleaned himself up to outperform Medich. Brett did too, but did most of his pitching for Chicago, to whom he was traded for Carlos May, who served as an excellent DH for the Yanks in ’76. Randolph hit .267/.356/.328 as a 21 year old. The Yankees went to the World Series. Stennett hit .257/.277/.341, Medich was hurt and ineffective, and the Pirates finished 9 back of the Phillies. Given their performances in ’76, it’s likely that the Pirates win the NL East if they don’t make that trade. Terrible, terrible deal.

11) Phil Rizzuto (.273/.351/.355, 93 OPS+, 41.8 WAR)

Scooter gets a bad rap because he’s probably not Hall of Fame worthy as a ballplayer (though given his overall contributions to the game as a player, broadcaster, and character, TCM’s glad he’s in). He’s in the hall basically because he played in nine World Series in 13 seasons (and won seven of them), and came out of nowhere to win a completely deserved MVP award in 1950, when he somehow hit.324/.418/.439. In reality, he was a very good shortstop and solid player who missed three full seasons of his prime due to World War II.

10) Mariano Rivera (74-55, 559 saves, 2.23 ERA, 205 ERA+, 52.9 WAR)

When is a closer worth more than a Hall of Fame SS? When that closer is Mariano Rivera, who boasts the 13th lowest ERA and the best ERA+ all time for pitchers with more than 1000 innings pitched. You’ve seen them before, but here are Mo’s postseason numbers one more time for posterity. 94 games. 139.2 innings. 8 wins. 1 loss. 42 saves. 13 runs allowed. 0.71 ERA. 109 strikeouts. 21 walks. 86 hits. 2 home runs allowed. Amazing.

If we take everything into account, Bill Dickey may have done more to promote the Yankee dynasty than anyone other than Babe Ruth. Dickey was a remarkable catcher for 17 years, with tremendous line drive power who developed homerun power late, and along with it a good eye. After he retired, he taught Yogi Berra the finer points of catching, ensuring the Yankees a huge competitive advantage, a slugging catcher, for another 18 years. And when the Yanks signed and groomed Elston Howard to replace Berra, Dickey taught him as well. There was a direct line from the Yankees of the late 1920s until the end of the dynasty in the mid-60s. And that line was Bill Dickey. Dickey also lost two years at the tail end of his career to the war.

8) Red Ruffing (231-225, 3.47 ERA, 120 ERA+, 60.6 WAR)

Frankly, TCM is kind of shocked by how high he ranks. For one thing, his overall ERA+ and record are significantly affected by his disastrous years pitching for Boston and Chicago (for whom he went a combined 42-101). The Sox were a terrible team overall, and particularly brutal on defense, such that Ruffing’s FIP was significantly lower than his ERA for them. But his time with the Yankees was excellent, especially two dominant campaigns in 1937 and 1939, when his ERA was 50% below the league average. He also gets an extra 10.9 WAR for being, perhaps, the best hitting pitcher in league history (.270/.312/.388 with the Yankees). Ruffing also missed three seasons at the tail end of his career while he served in the Air Force. He was still a good pitcher before he went in, and was a good pitcher (in small doses) when he got out. He also went 7-2 with a 2.63 ERA in 10 World Series starts.

7) Yogi Berra (.285/.348/.483, 125 OPS+, 358 homers, 61.7 WAR)

It is a testament to Yogi Berra the player that Yogi Berra the character never subsumed him. Berra the player is still generally remembered in the same breath because he was so damn good. From 1950-1956, Berra won three MVP awards and finished in the top four of voting each time. The Yankees barely needed a backup catcher in that span. Berra caught 148 of 154 games in 1950 and 1954, and topped 140 games caught (on a 154 game schedule) five times. If you don’t like Yogi Berra, The Common Man doesn’t like you.

6) Whitey Ford (236-106, 2.75 ERA, 133 ERA+, 55.3 WAR)

You know what’s really confusing? When you can’t find stories from the very start of Whitey Ford’s Major League career because you’re searching for “Whitey” Ford when all the papers were still calling him “Ed.” Whitey already had his nickname when he was called up on June 29, 1950, but it wasn’t widely used until mid-August and September, when Ford completed 7 of 8 starts with 7 wins and a 1.70 ERA. Another nickname, TCM’s personal favorite, The Chairman of the Board, seems to have been coined by Elston Howard in 1961, or at least that’s when it began appearing in the papers. He also was apparently called “Slick” by his teammates around the same time, though that generally didn’t make it into the press. The Common Man continues to think that Ford’s career was curtailed when Casey Stengel was let go after 1960. New manager Ralph Houk decided to use his thoroughbred like a plow-horse, going from an average of 205 innings/year from 1953-1960 to 260 innings/year from ’61-’65. Ford was hurt and pitched sparingly in ’66 and ’67 before retiring. He also missed two years after his brilliant rookie campaign for the Korean War.

5) Derek Jeter (.314/.385/.452, 119 OPS+, 234 homers, 323 stolen bases, 2926 hits, 12 kittens rescued, 38 babies delivered, 4 murder convictions overturned using new DNA evidence, and 70.1 WAR)

All snark aside, Derek Jeter has been a fantabulous player. Not a great fielder, but still a fantabulous splendicular player. The kind of player you have to make up words to describe. When Derek Jeter was eligible for the draft, Hall of Famer Hal Newhouser was working for the Astros and urgently insisted Houston take him with the first overall pick. Houston thought he’d cost too much, and worked out a deal with Phil Nevin to take $700,000. Jeter was taken by and signed with the Yanks, at #6 overall, for…wait for it…$700,000. Newhouser was so angry he quit. Can you imagine an Astros double play combination of Jeter to Biggio to Bagwell? Meanwhile, the starting SS from 1995 to 2007 were Orlando Miller, Tim Bogar, Ricky Gutierrez, Julio Lugo, and Adam Everett.

4) Joe DiMaggio (.325/.398/.579, 155 OPS+, 361 homers, 1537 RBI, 83.6 WAR)

DiMaggio did miss three full prime seasons to World War II, but it’s still almost impossible that he would have moved up the list further, the top 3 Yankees are so good. By all accounts, Joe DiMaggio was an easy man to admire but a very hard man to like. One of his only friends was Lefty Gomez, but then Gomez got along with everybody. Ed Lopat called him “the loneliest man I ever knew. He led the league in room service.” DiMaggio also knew a little something about acrimonious contract disputes. 1938, 1941, 1942, 1949. Joe held out darn near every year for more money. Not that we should blame him. He was an exquisite player, and in the labor system at that time holding out was the only way to get more money.

3) Lou Gehrig (.340/.447/.632, 178 OPS+, 493 homers, 534 doubles, 1995 RBI, 118.4 WAR)

Not to tear apart the Lou Gehrig creation story further, but Gehrig had been under contract with the Yankees since June of 1923. He was clearly being groomed to play 1B for the Yankees. That summer, just 20 years old, he hit 24 homers in 59 games for the Hartford Senators and earned a call-up where he hit .423/.464/.769 in 29 plate appearances. The Yankees wanted him to get more seasoning, so they sent him back to Hartford where he was again dominant. The question was never whether Gehrig would replace Wally Pipp, but when. The Yankees had boundless faith in their young slugger. Indeed, after Gehrig’s big 3 for 5 day on June 2nd, 1925, to start his streak, he went hitless in two straight games and dropped his season line to .200/.263/.286. If the goal was simply to give Pipp a day off or two, surely the Yanks would have let the veteran come back after two straight 0 for 3s. Instead, they let the kid keep playing, signifying that, in reality, the Yankees had made the decision to hand the job to Gehrig for the rest of the year.

And why not? The Yankees were 16-26, 13.5 games back of the A’s (they’d finish 69-85). Babe Ruth had just made his season debut the day before after stomach ailments cost him the first two months of the season. It was time to let youth be served, and let the Yankee brass see what the team would look like in 1926 and beyond. 1925 featured the first real action for Gehrig, Earle Combs, Mark Koenig, Hank Johnson, and less successfully, Benny Benbough and Pee Wee Wanninger. Pipp didn’t lose his job because he had a headache and Gehrig took off. He lost it because the Yankees decided they weren’t going anywhere, weren’t enamored with their first baseman, and decided to build for the future. If Gehrig hadn’t gotten sick and been forced out of the game at 36, he would have easily been #2 on this list.

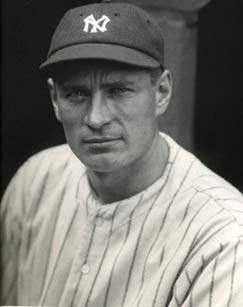

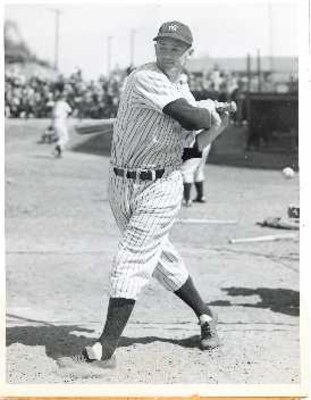

2) Mickey Mantle (.298/.421/.557, 172 OPS+, 536 homers, 1509 RBI, 1676 runs, 2415 hits, 120.2 WAR)

The Common Man is going to get to Jane Leavy’s biography of The Mick as soon as he finishes the biography of Jackie Robinson he’s reading. He won’t be surprised if he learns that baseball wasn’t all that fun for Mantle, actually. His dad was apparently a real son of a bitch who forced his son to learn to switch hit at the age of 5 and pushed him to become a ballplayer. All the injuries Mantle sustained, especially the destruction of his knee ligaments in his rookie season, probably made baseball a slog. And he constantly was playing in the shadows of Joe DiMaggio and Babe Ruth, which must have added a ton of pressure he didn’t want nor need. But maybe not. Maybe the Mick still loved the game. But it sure seems like the game chose him rather than the other way around. What a beautiful ballplayer. TCM’s favorite stat, by the way, is that Mantle scored more runs than he drove in because of his incredible patience. And as TCM argued before, he probably could have continued playing productively for another couple of seasons if he had wanted to, but the rise of the pitcher at the end of the 1960s masked his continued greatness.

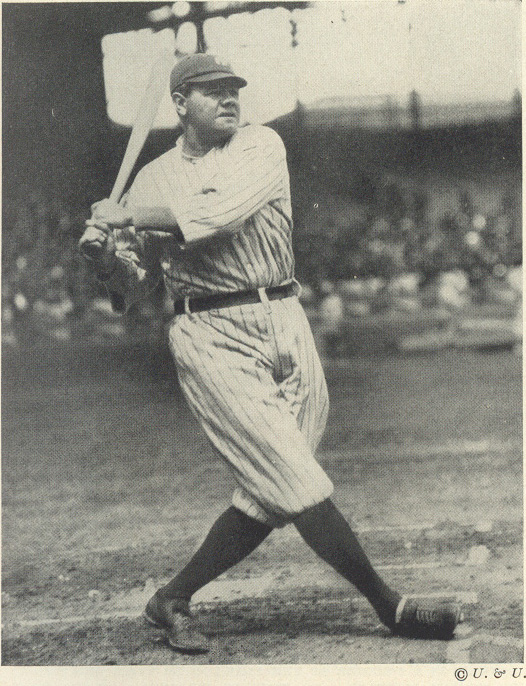

1) Babe Ruth (.349/.484/.711, 209 OPS+, 659 homers, 506 doubles, 136 triples, 2174 runs, 2213 RBI, 2518 hits, 149.6 WAR)

Who else could it be? There has never been another person in the history of America like Babe Ruth. He was unique. A man defined by his skill, his feats, and his excess. He is, at once, all that is right and wrong with America. He was wonderful with and to children. He was unmatched with the bat, and an incredible, perhaps Hall of Fame quality pitcher. He was super-humanly strong. He rose up from nothing to become the most famous man in America. He didn’t care about color, and would barnstorm with anybody. And he was generous to a fault with total strangers. But he was also angry and violent. He didn’t take care of himself or plan for the future. He was arrogant. He consumed on a level probably only rivaled by Michael Jackson or Elvis Presley. He was childish and petulant. He was jealous and resentful. You can’t help but love the man, but damn it if he didn’t make it hard sometimes.

.jpg)

%201939-2T.jpg)

22 comments:

Goodness gracious. I didn't know Babe was THAT dominant in Pinstripes.

"staying healthy is a skill"

I think I disagree with this.

"Frankly, TCM isn’t sure what to say about Roy White"

You could talk about how Bill James has argued that he was a better player than Jim Rice.

But oh that one loss for Rivera was a good one for non-Yankee fans.

What a great list! Thank you for doing this.

Re: Mantle, it was pretty unanimous when he retired that he was still the best player on that (lousy) team. Oh well.

Enjoyed the list. One minor correction: Shawkey won four games in six days in 1919. On June 3rd of that year, he was not credited with a win. These days, he would have been given a save. See:

http://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1919/B06030PHA1919.htm

35+ year Yankee fan here...great post. Really enjoyed the capsule summaries of the players I did and didn't get to see. Also while I was a Mattingly/Munson guy, I can't argue with the rank of Willie Randolph, who was steadily terrific for the Yankees all those years.

Any thoughts on where Arod will ultimately wind up on this list?

Thanks for all the comments so far. A couple of notes.

@Bill Maybe TCM went too far. That said, it would seem unfair to ignore Mattingly's back issues as they relate to his overall value and "greatness" and ignoring how more often someone like Willie Randolph was able to be on the field and help the team.

@Tom Ruane Tom, thanks for doing some digging, but you missed something. Shawkey won games on May 29, 30, 31, and June 2 of 1919 (giving him 4 wins in 6 days, as the article mentioned), and then pitched an inning to get what we would consider a save on June 3. A busy man, Mr. Shawkey.

@Eric Hard to say. He's signed for 7 more years, and obviously won't be traded anywhere in that time. But his performance has slipped precipitously over the last three years. He's probably got about 15-20 Wins Above Replacement left in him, which would end up slotting him somewhere between Bill Dickey (#9, 54.4 WAR) and Red Ruffing (#8, 60.6 WAR).

Oh, I don't disagree that Randolph places ahead of Mattingly, or that Mattingly's failure to stay healthy is part of why. I just don't think it's a skill (Nick at nickstwinsblog.com had a great post up about this just yesterday, linked in this morning's roundup). I think it's mostly bad luck.

It nonetheless happened, and still hurts Mattingly's overall value.

What a fun read. Thanks so much for a pleasurable twenty minutes this morning. Great. Super.

He wallops the curve with vim and verve

From Texas to Duluth

Which is no small task, and I rise to ask

Was there ever a guy like Ruth?

Sorry, I can't remember the original author -- might've been Fred Lieb

Oh, and btw -- if you're going to credit Chandler for losing war years, you should also ding him for piling up big years during the wars against a watered-down league.

No Dave Winfield? Really?

@ Devin

TCM's a Minnesota native, so he has no bones to pick with Winnie. It's just a tough group to break into. Winfield had 25.6 WAR as a Yankee over 9+ seasons (one of which he missed for back surgery). His defense was bad and never hit as well as you think he would have. In terms of career value, Dave Winfield is great. In terms of his time with the Yanks, he was only pretty good.

Well done, but how can you have this list without Winfield or Reggie? Yes, Reggie did not play as long as others, but I think you put too much emphasis on the length of time played. Reggie burned very brightly as a Yankee. I think it is safe to say they were both a tad better than Wally Pipp and Charlie Keller.

First of all, as a Yankee Charlie Keller could hit circles around Winfield, and was better than Jackson. Both Reggie and Winnie are big names, and Jackson's performances during the '77 and '78 World Series were terrific. But both were bad defensive players, and Jackson spent 135 games at DH. Frankly, Jackson's 16.5 WAR doesn't even come close to sniffing this list, even when we take into account his postseason heroics. The Common Man respectfully submits that you're placing too much of an emphasis on fame and on the recent past.

Anyone who saw Henderson tank on the Yankees when he wanted out would not rate him nearly so highly. He was a greatly talented player, no doubt much more skilled than Mattingly when they were both at their best, but the last year he was with them was disgraceful enough that he should never be includked on this list.

@Dave

He may have been unhappy, but you're underestimating his play. He played his usually great defense, posted a .392 OBP, but looks bad because of a .270 BABIP, which was his worst mark ever until 2001, when he was 42. Ask yourself, why in the hell would Rickey deliberately slouch during a contract year? Did he ever do that anywhere else?

Nice post.

Re: Mattingly, he's my all-time favorite player, but even I don't think he should be in the Hall. But you should know part of the Hall anger is (as usual) worse players being in.

Kirby Puckett got 82% of the vote, Mattingly 28% at his peak. James has Mattingly as the most similar hitter to Puckett. Heck, they were practically the same hitter if you look at career stats.

Puckett played a more important position defensively (although according to B-R, played it worse) but he's basically in because of two World Series titles and "We'll see you tomorrow night!"

Which is fine, I guess. But should it account for a 54%-72% difference in vote totals?

Excellent list, although I'd have to move Yogi up to #5, Jeter to #6, with Ford at #7. Both Yogi and Jeter play two of the toughest positions on the defensive spectrum, so they get extra points for that, yet Catcher is the most difficult, and Yogi is rated either #1 or #2 on MLB's all-time list for catchers, so I'll put him ahead of Jeter.

What to say about White? Like Nettles, his career took place during a low-offense period, yet at his peak he was good for near 20 HRs, at time when that meant something. A switch hitter with a very good eye, as you noted; a good baserunner with good speed; a line-drive hitter with surprising power for his size; and as a fielder he covered a lot of ground in a big left field. Many Baby Boomer's memory of White comes toward the end of his career when the Yankees returned to the World Series, when he wasn't quite the player he was at his peak.

And as for Mattingly, you're probably a little light on the rating. There is a similarity between Mattingly and Keller. Both were HOF-caliber players whose careers were shorted by back issues. Mattingly was regarded by his peers at the best in the game at his peak, and did twice lead the league in OPS+, and his 147 OPS+ was the highest of any first basemen in the 1980s. It's generally understood that most advanced defensive statistics do a very poor job of rating 1B, and that impacts WAR and Mattingly. Bill James had him as the 12th greatest first baseman all time in his Historial Baseball Abstract. That was based on his Wins Shares system, which he's revised. I'm guessing he has Mattingly a few slots lower, not to mention a few other first baseman have now moved up the list. So while I think James was overly agressive in his Mattingly rating, I think yours goes a bit too far the opposite direction, but I do put more value on peak when raitng players. I'd probably put him about five slots higher.

That said, great list.

I'd have to have Berra higher, up above Jeter. Taking into account position, he really deserves it up there with the true biggies.

Great list. One nitpick: It's Benny Bengough, not Benbough

I think if Munson had not perished in that plane crash, the Yankees would have won it all in 1980 vs Philly.

Where they really missed him was the LCS that year vs K.C., a team the Yankees had knocked out three straight years from 76-78. Reggie had gotten the headlines, but Munson was clutch and you could tell in that series that Munson's bat was really missed in that series vs the Royals. Yeah, they won 103 games, but in October, they really missed Munson.

Even more so in the 1981 World Series vs the Dodgers when Winfield struggled in that series and Reggie was hurt. Again, here's where Munson was really missed. When those guys struggled, Munson would come up big in the clutch.

I also think 80 and 81, would have been the last hurrah for this group. They were getting long in the tooth, and Munson was on the down side of his career anyway. I think he would retired after the '81 season.

Post a Comment