By The Common Man

Because the Respendent Jeter deserves to be honored (often with a pilgrimage to hear him hold forth on matters great and insignificant), The Common Man presents the companion to his earlier piece on the 40 greatest Yankees with this look at the 40 greatest shortstops.

Because the Respendent Jeter deserves to be honored (often with a pilgrimage to hear him hold forth on matters great and insignificant), The Common Man presents the companion to his earlier piece on the 40 greatest Yankees with this look at the 40 greatest shortstops.

A couple of notes about methodology first, however. One, if a player spent more than half of their career at another position, he is not included on this list with the exception of Ernie Banks (because, c'mon, it's Ernie Banks). Also, all statistics are based on career totals and value, not on time spent specfiically at SS. So, Robin Yount, for instance, gets credit here for all of his career, not just his time in the infield. Frankly, it was easier this way, rather than trying to parse and split hairs. If TCM ever updates this list, he may revise his methodology, as that would seem to be a legitimate criticism of the rankings. So without further delay:

40) Jay Bell (.265/.343/.416, 101 OPS+, 195 homers, 34.8 WAR)

Before his major league career began, Jay Bell was traded with three other players for Bert Blyleven. In 1986, he got called up at the end of September and started the last five games for the Indians. In his first at bat, he hit the first pitch he saw for a solo home run. The pitcher was Bert Blyleven. Bell was always a perfectly decent hitter, especially for a shortstop. But in 1999 he had

39) Rico Petrocelli (.251/.332/.420, 108 OPS+, 210 homers, 35.6 WAR)

Rico spent almost as much time at 3B as SS, so he barely qualifies for this list. Before researching Petrocelli, The Common Man admittedly didn’t know much about him. But this story makes TCM like him a lot, since The Uncommon Wife just got out of the hospital due to a staph infection. In 1966, Petrocelli was married with an infant son and one day his wife gets a terrible pain. She urges him not to miss the game, and sends him to the ballpark. Petrocelli sits there and stews, and by the 8th inning he’s about to burst. So he just leaves with two innings to go. “I was wrong, I should have stayed. I was stupid and just lost my head, but I left and when I walked in my door there was Elsie on the stairs. She was lying on the floor. I took her to the hospital and they said she’d had a cyst that had just broken.” The next day, Herman reported to Tom Yawkey, “[Manager Billy] Herman was in with him and I apologized to him, but he took me down to his office and told me he was fining me and when he told me how much ($1,000 of Petrocelli’s $10,000 salary), God, I almost died.”

Herman apparently hated Petrocelli. That summer, just before Herman was fired, he told reporters, “If I’m fired, it’s because of Petrocelli. If he hadn’t quit on us, we’d have won 10 more games." In other news, Billy Herman sounds like a real ass.

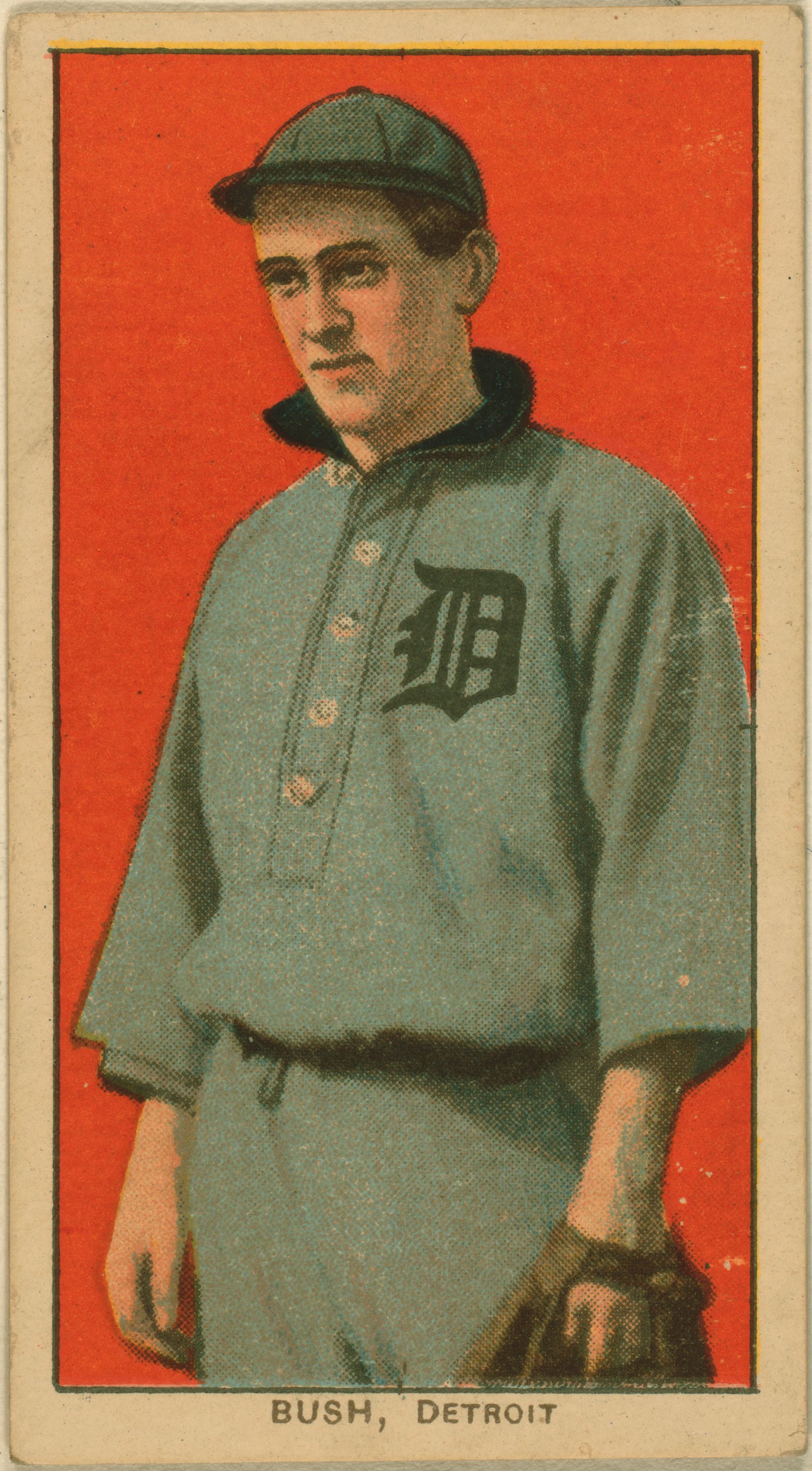

38) Donie Bush (.250/.356/.300, 91 OPS+, 406 stolen bases, 37.2 WAR)

Bush averaged about 96 walks a year. That’s remarkable, especially for someone with absolutely no power. It helped that he was only 5’6”. Think of him as the player everybody thinks David Eckstein is. Bill James wrote in his New Historical Abstract that Bush was absolutely terrible about turning the double play. “For the thirteen seasons that Bush was their regular shortstop, the Tigers were almost 300 double plays below expectation.” Later, James writes

“Bush’s career was during an era of rapidly increasing double plays. An average team when Bush broke in would turn about 85 double plays per season. Bush apparently never adjusted; he continued to think about ‘being sure you get one,’ which was the prevailing idea at the beginning of his career. It cost him dearly, because in modern baseball you can’t win if you can’t turn two.”37) Dick Bartell (.284/.355/.391, 96 OPS+, 442 doubles, 34.4 WAR)

Nobody liked Bartell all that much. He never stayed anywhere longer than a few years before he wore out his welcome. In 1940, in a challenge trade for Billy Rogell, Bartell was sent to the Tigers. He had a bad season offensively, though was lauded for his play until the World Series. In the seventh inning of Game 7, Frank McCormick was on second base when Johnny Ripple doubled off the right field wall. From the AP game recap the next day,

“McCormick, figuring the ball might be caught, held second until he saw it hit safe, and then tore for third. Campbell made a quick recovery in right and whipped the ball to Bartell in the vicinity of second base. It would have been a cinch to cut McCormick down at home. But for some reason…Bartell just caught the ball and examined the seams and looked at Ripple, who just reached second.”Rippel then came around to score with 2 outs and the Tigers lost by a run. Bartell was labeled the series goat in the press, though his team said nothing. The next year, Bartell started out just 2 for 12 in his team’s first five games before being benched for more than a month. Eventually, he was released and the Giants picked him up and he posted 120 OPS+ the rest of the way and revived his career. Rowdy Richard missed two seasons at the tail end of his career to World War II.

36) Alvin Dark (.289/.333/.411, 98 OPS+, 126 homers, 38.5 WAR)

Dark made the unusual move of going straight from his playing career to the manager’s seat. He retired from the field after 1960 and was named manager of San Francisco before November. He was terrifically successful, winning 85 games and finishing 3rd. In 1962, he piloted the Giants to 103 wins and the World Series. Dark probably got a late start on his career due to World War II, though he still spent all of 1947 in the minors.

35) Tony Fernandez (.288/.347/.399, 101 OPS+, 414 doubles, 246 stolen bases, 39.6 WAR)

The Dominican Republic is known as the land of shortstops. It’s just that so many of them are really the same all field, no hit models, and not very good players. The first Dominican SS, Roberto Pena, debuted as early as 1965, and became a regular (in the familiar no hit, all glove mode) as a 31 year old in 1968. And a few shortstops debuted in the mid-70s, similar players like Frank Taveras, Mario Guerrero, and Alfredo Griffin. But the trend didn’t really begin in earnest until the 1980s when guys like Rafael Ramirez, Julio Franco, Rafael Belliard, Jose Uribe, Manny Lee, Mariano Duncan, and Tony Fernandez came up. Franco and Fernandez, really, were the only players in that group to have any offensive success, and both put their games together more or less at the same time in 1985. Since then, Juan Bell, Andujar Cedeno, Neifi Perez, Deivi Cruz, and Ramon Santiago have done little to dispel the stereotype. Indeed, given that Franco had to move off of SS relatively quickly, the only real offensively acceptable shortstops to come out of the Domincan have been Fernandez and Miguel Tejada. That’s a pretty sad track record for one of the hotbeds of baseball talent in the world, and perhaps speaks to a counterproductive emphasis on defense to the detriment of offense as part of the training in Dominican academies.

34) Ed McKeon (.302/.365/.417, 114 OPS+, 324 stolen bases, 40.0 WAR)

Bill James ranks Ed McKean as “the weakest defensive player listed among the top 100 shortstops.” And it’s true that McKean was one of the least sure-handed players in baseball history. Among players with more than 3000 plate appearances, McKean ranks 251st out of 264 in fielding percentage. Fielding percentages were much lower in the 19th century, of course, but McKean combined that with an apparent lack of range as well. But a 114 OPS+ from your shortstop covers up a lot of problems, and McKean’s teams all finished with winning records after 1892, so the tradeoff must have been worth it.

33) Roger Peckinpaugh (.259/.336/.335, 86 OPS+, 40.4 WAR)

No one has ever had a worse World Series than Roger Peckinpaugh had in 1925. Named AL MVP just before the Series, Peck made the voters look bad by hitting just .250/.280/.417 while making 8 errors in 7 games, including two crucial mistakes in Game 7 that led to four unearned runs and gave Pittsburgh the game and the Series. However, if he’s to be believed, a bad call two days earlier extended the Series and took Peck from hero to goat. On October 13, with his team up 3 games to 2, Peck helped put the Senators up 2-0 after he doubled in Ossie Bluege. In the bottom of the third, Eddie Moore led off with a walk when Max Carey hit a grounder to short. The next day, Peckinpaugh wrote a syndicated article that describes what he believes happened,

“Umpire Moriarty yesterday missed one at a critical time which beat us, and for this reason, I cannot help but mention it….On Carey’s grounder to me, I beat Eddie to second, by a full step, yet he was called safe. Naturally my arguments over the decision were just so much wasted words. Cuyler’s sacrifice moved both runners along, one scoring on an infield out and the other on Traynor’s single, after Barhart had grounded to Bluege. Had we got this decision-which we were entitled to, neither would have scored.”Peckinpaugh was not charged with an error on the play, which was called a fielder’s choice, though he did make a throwing error later that game. The next day, he, Muddy Ruel, and Bucky Harris (all of whom had been quoted in the article) were called before Moriarty and Judge Landis, who demanded an apology. It’s not clear whether they did or not, nor is it clear that Peck’s right about the play in question. Either way, wouldn’t it be nice to have had instant replay?

32) Miguel Tejada (.287/.339/.462, 110 OPS+, 300 homers, 447 doubles, 42.0 WAR)

Tejada’s allegedly going to play shortstop again this year, which is a little like saying the Italian army is going to be defending Southern Europe. Technically, they’re both going to be in position, but if there is any kind of urgent need, neither has a hope of performing as advertised. Tejada was a great player for exactly one season, but not the year he won the AL MVP. However, he was consistently good for eight straight seasons and has been incredibly durable, having played fewer than 156 games just once in the last 12 seasons. Despite what may be a rough season in San Francisco this year, he’s capable of pushing up five more spots on this list by the end of 2011. As far as TCM knows, he's the only man on this list who's been guilty of perjury.

31) Nomar Garciaparra (.313/.361/.521, 124 OPS+, 229 homers, 42.6 WAR)

Remember the big three? God, Nomar was good. Through 2000, Nomar had played four full seasons and had hit .333/.382/.573 (a 140 OPS+), while playing completely acceptable defense at SS. That wrist injury in 2001 left him a great player where there had once been a transcendent one. He and Jeter were the same age, and Jeter had hit .322/.394/.468 (a 122 OPS+) through that stage while giving back runs at short. Had his wrist held, and A-Rod moved to 3B as he did, Nomar might be considered one of the four or five best shortstops ever. Just an amazing and deadly player.

Don’t let the low raw numbers fool you, for the Deadball Era, Fletcher was a heck of a weapon for John McGraw. He was a strong fielder who could hold his own offensively thanks, in part, to a willingness to take one for the team. Fletcher led the NL in HBP in five of six seasons from 1913-1918. Fletcher was traded from the Giants to the Phillies in 1920 for Dave Bancroft. The trade was a disaster for Philadelphia. Bancroft went on to lead the Giants to the 1921 Series, and Fletcher retired after the 1920 season ostensibly to look after the death of his father and brother (though the prospect of playing for a 103 loss team probably wasn’t very appealing). He did come back to play in 1922, but the Phillies, as they would be for years to come, were terrible.

29) Omar Vizquel (.273/.338/.354, 83 OPS+, 2799 hits, 43.1 WAR)

Omar Vizquel is currently 201 hits away from 3000. That boggles the mind. If he makes it, he will have the lowest batting average, lowest on base percentage, and lowest slugging percentage of any player on the list. He will have fewer home runs than any player on the list than Eddie Collins and maybe Napoleon Lajoie (who’s still 2 ahead of Omar). Omar Vizquel is engaged in a war of attrition to make it to the Hall of Fame, and he appears to be winning. The Common Man cares very little for whether he makes it or not (though if he does make it, TCM prays that Barry Larkin and Alan Trammell will too); but if he does, Vizquel will almost certainly be the worst shortstop in history to make it. His defensive skills, while rightfully lauded in his prime, are grossly overstated today. The man could not hold a candle to Ozzie Smith. Nor was he as good as Cal Ripken or Phil Rizzuto.

28) Travis Jackson (.291/.337/.433, 102 OPS+, 135 homers, 43.3 WAR)

If Omar’s going to slide past anyone to avoid the ignominy of being the worst SS in the hall, it’s Jackson. Which is not to disparage Jackson. He was a fine shortstop. In his prime he was a great defender, and produced above average offense. But the era in which he played was full of high offense guys, and Jackson’s career was done by the time he was 32. In the early ‘30s, Jackson’s left knee started bothering him, culminating in a broken tibia that required significant surgery after the 1932 season. And he missed most of both 1932 and 1933, which would have been prime seasons for him. He never really recovered his range of motion afterwards and was released after an abysmal 1936.

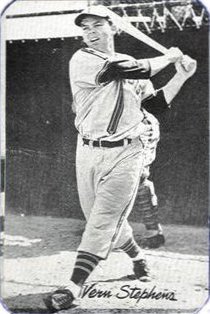

If Omar’s going to slide past anyone to avoid the ignominy of being the worst SS in the hall, it’s Jackson. Which is not to disparage Jackson. He was a fine shortstop. In his prime he was a great defender, and produced above average offense. But the era in which he played was full of high offense guys, and Jackson’s career was done by the time he was 32. In the early ‘30s, Jackson’s left knee started bothering him, culminating in a broken tibia that required significant surgery after the 1932 season. And he missed most of both 1932 and 1933, which would have been prime seasons for him. He never really recovered his range of motion afterwards and was released after an abysmal 1936.27) Vern Stephens (.286/.355/.460, 119 OPS+, 247 homers, 1174 RBI, 43.5 WAR)

Anyway, promoter Jorge Pasquel angered baseball officials enough that the New York Yankees and Giants attempted to get an injunction preventing Pasquel from contacting their players. Pasquel counter-sued and proclaimed that MLB contracts were “monopolistic, unconscionable, illegal, and against public policy.” Players signing such contracts, Pasquel argued to the New York Superior Court, were “in peonage for life.” Yankees counsel Mark Hughes rolled out the usual arguments that “the great American game as we know it will be destroyed” if the contracts were found illegal. For reasons that, TCM can’t figure out, the judge disagreed with Pasquel’s arguments and enjoined the Mexican League from contacting Major League players.

26) Herman Long (.277/.335/.383, 94 OPS+, 537 stolen bases, 1456 runs, 44.6 WAR)

A direct contemporary of McKean (see above), Long had much the same trouble holding onto the ball (again, largely because of the era). But he had much more range than McKean, and his teams tended to be better, winning five pennants in the 1890s. McKean was the better hitter though.

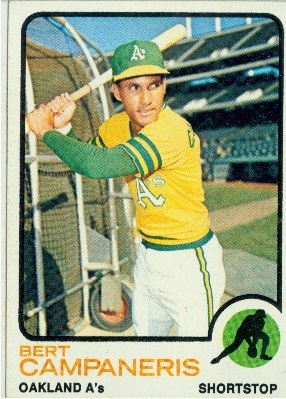

25) Bert Campaneris (.259/.311/.342, 89 OPS+, 649 stolen bases, 45.2 WAR)

That’s right, Bert Campaneris is better than Omar Vizquel. He was just a much better hitter and baserunner. In 1977, Campy signed as a free agent with the Texas Rangers for just short of a million dollars a year over five years. The club was terrifically successful that year, winning 94 games and finishing 2nd to the Royals. It was an 8 game difference, but surely they could have made up some of that ground had they not made Bert Campaneris sacrifice himself 40 times, more than any other player has sacrificed himself since 1929. Of those, 34 came from June 28 on, when Billy Hunter took over the club. Hunter, as TCM has pointed out before was a terrible hitter who undoubtedly thought every shortstop was a bad hitter and needed to move runners up. After all, that’s basically all a guy with a 53 career OPS+ was good for. Over a full season, that works out to a 59 sacrifice pace, which would have the third highest total ever. Billy Hunter went 60-33 for the Rangers that year. How well would he have done if he hadn’t given away more than a game of outs by his million dollar SS?

24) Jim Fregosi (.265/.338/.398, 113 OPS+, 151 homers, 46.1 WAR)

Jim Fregosi deserves to be more than an historical footnote to Nolan Ryan’s career. He made the All Star team 6 times in 7 years, and was a good offensive player given his era. Bill James thought, if he had played in the ‘90s, he would have hit 30 homers a year. That’s probably an exaggeration, but he would have had a Nomar-lite career. In 1971, Fregosi developed a sore foot. Sent home for examination, Fregosi was startled when doctors discovered a nauroma, or “a tumor on the nerve ending between the big toe and the second toe.” That sounds incredibly painful. But he refused to get surgery on it until July, and basically never recovered. He never got more than 400 PAs again.

23) Hughie Jennings (.312/.391/.406, 118 OPS+, 359 stolen bases, 46.4 WAR)

Hughie Jennings is one of The Common Man’s favorite players from the early days of baseball. He was a terrific defensive shortstop, infectiously enthusiastic, indifferent to the rules, and incredibly adept at getting hit by pitches, including 143 times in a three year span. One has to conclude that that probably contributed to the early end of his career, as his skull was fractured three times. Knowing what we know now about concussions and head injuries, it’s likely that all the shots to the head contributed to Jennings’ drinking and relatively early death (at 59).

22) Dave Bancroft (.279/.355/.358, 98 OPS+, 46.4 WAR)

Bancroft picked a great time to have the best four seasons of his career. Bancroft raised his game to a new level after being traded to the Giants for Fletcher, and the Giants corresponded by making it to the World Series in each of the next three seasons, winning two of them. Bancroft was terrible in all three series, hitting .172/.220/.183 in more than 100 plate appearances. He also picked a great time to be a Giant, as Frankie Frisch was there and is largely responsible for Bancroft making the Hall of Fame. Bancroft wanted to be a manager, so he was traded to the Braves after 1923 and was their player/manager for four years. In 1930, he returned to the Giants and served as the interim manager whenever John McGraw was too sick, but team owner Horace Stoneham had no confidence in Bancroft as a manager long term. When McGraw retired, he named Bill Terry as his successor. Bancroft was, understandably, disappointed and he resigned.

21) Joe Sewell (.312/.391/.413, 108 OPS+, 2226 hits, 48.4 WAR)

For someone who never struck out (114 times in 14 seasons), Joe Sewell was definitely not flailing away at the plate. What’s most remarkable about Sewell is not necessarily that he had 7 seasons with fewer than 10 strikeouts, but that in those seasons he managed a BB/K ratio of more than 10 to 1. This includes an incredible 18.7 to 1 ratio in 1932 when he struck out just 3 times in 576 PAs, and walked 56 times. That’s crazy.

20) Joe Tinker (.262/.308/.353, 96 OPS+, 336 stolen bases, 49.2 WAR)

So much for the notion of team chemistry. Tinker and Evers famously didn’t talk for a year. And Evers had the reputation as “The Crab,” but Tinker wasn’t exactly a barrel of monkeys either. In 1914, Tinker was made the player/manager of the Reds. It was his first gig. It did not go well. The team finished 64-89 and in 7th place. And Tinker and the team president feuded more or less constantly. Tinker took his grievances to the press in August,

“I realize that I must take a stand with regard to the management of this club or step down and out. The showing of the team has been a great disappointment to all concerned, and I have held off as long as I could because I felt that I am not a success myself, so far as I have gone; that the club has not been making money, owing to its low standing in the race, and therefore that it was up to me to stand for some things that I would not otherwise have endured. But when I found that our players were being sold outright to minor league clubs without options, and that I was constantly being urged to cut off players against my best judgment without waiting for a chance to make a trade which would help the team, I decided that I must make a stand.

If this statement does not meet with the approval of President Herrmann I can’t help it, and he as the right to let me out at any time. I would rather go out to my fruit farm in Oregon than try to handle a club when I am not backed up by the owners. So long as I continue manager, I shall not let another player go unless I know just what the deal is. I greatly admire and respect President Herrmann personally, but his ideas of building up a ball club do not correspond with mine.”The Reds arranged to release him to the Dodgers after the season, but Tinker jumped to the new Federal League where he would have total control of his Chicago club.

19) Luis Aparicio (.262/.311/.343, 82 OPS+, 2677 hits, 506 stolen bases, 49.9 WAR)

Today, you’ll often hear about players from Venezuela living with the threats that their loved ones will be kidnapped and held for ransom. This is not a new problem. During Spring Training in 1973, Aparicio went through the same thing. According to the Pittsburgh Press, “Police in Maracaibo, Venezuela, are keeping the 15-year-old son of Luis Aparicio under constant guard because of threats that he would be kidnapped, the Boston Red Sox star says….’I’m not only worried about him, but I worry about everybody. I’ve got four more (children) at home…. The police don’t know who is doing it or why they’re doing it, outside of the money.’” He was making roughly $100,000 at the time. Luis still had a solid season, but retired and returned to Venezuela immediately after it was over. Can you blame him?

18) Phil Rizzuto (.273/.351/.355, 93 OPS+, 41.8 WAR)

17) Lou Boudreau (.295/.380/.415, 120 OPS+, 385 doubles, 56.0 WAR)

Boudreau got named the Indians player-manager at 24 years old, after just two good Major League seasons. It was a little as if Andrew McCutchen was named manager of the Pirates this offseason. The results were predictably mixed. He finished above .500 in six of his nine seasons in charge of the Tribe, and won a World Series when he was paired with the risk-taking Bill Veeck as the team’s owner in 1948. Veeck brought in Larry Doby and Satchel Paige, and traded for Joe Gordon and Gene Bearden. His relationship with Paige was complicated. Boudreau tried to run a tight ship, and Satchel had a strong independent streak. Satchel wouldn’t run, violated curfew, and refused to ride the bus with the team. At the same time, his pitching was pretty terrific, particularly in 1948, and he always called Boudreau, who was 11 years younger, Mr. Lou. It was a weird relationship, and one probably more or less “colored” by the era in race relations in which it was developed.

16) Jack Glasscock (.290/.337/.374, 111 OPS+, 372+ stolen bases, 1164 runs, 58.7 WAR)

Jack Glasscock.

Done snickering? No? Take your time. Now? Good.

Anyway, Bill James has Glasscock ranked as the 43rd best SS in history. That’s probably the biggest disparity between his list in the New Historical Baseball Abstract and this list. Bill calculates that “Pebbly Jack” deserved four Gold Gloves between 1880 and 1890, and it’s clear he was one of the more careful fielders of his day. He got his nickname by making sure that his portion of the infield was as free of rocks and stones that could alter the path of the ball as possible. Coupled with some truly strong offense at his position, it’s hard to tell why James discounted him so heavily. According to Harold Seymore, Glasscock was considered a traitor to the Brotherhood of Players who were organizing the Player’s League. Oddly, he had jumped to the Union Association in 1884, and perhaps soured by that experience, saw little chance in the Players Revolt succeeding.

Bobby Wallace’s career spanned 25 years. He started out in 1894 for the old Cleveland Spiders before becoming the first superstar of the St. Louis Browns. He was a very strong fielder, who old-timey pitcher Bob Wickard said, “covered more ground than the great Hans Wagner, and got the ball away to the base faster than any other infielder of his time.” He also was a strong hitter playing a premium defensive position. It’s unclear what spurred his induction into the Hall of Fame in 1953, though he certainly seems deserving by these metrics.

14) Joe Cronin (.301/.390/.468, 119 OPS+, 170 homers, 2285 hits, 515 doubles, 1233 runs, 1424 RBI, 62.5 WAR)

It’s widely known, of course, that Joe Cronin was Clark Griffith’s son-in-law when he was dealt in 1934. What’s generally forgotten is that Cronin had been married to Griffith’s niece (who Griffith had adopted) just weeks before the sale. Must have been a disappointing reception. Cash bar. Macarena. Etc.

Cronin initially came up as a middle infielder with the Pirates during their great run in 1927, but was allegedly benched for making three errors in the field. Baseball Reference has no evidence of those errors, so it’s unclear what’s going on here, but Cronin didn’t start another game until the very last one of the season.

Here The Common Man needs some reader help. Cronin was generally considered an excellent fielder in his early career, with good range. TCM remembers reading somewhere that during the course of his career Cronin adopted the curious habit of always dropping to one knee to field the ball, which angered his teammates (particularly his pitching staff). His range did seem to decrease upon his trade to the Red Sox, but his double plays remained relatively steady. Anybody who can confirm this for TCM would get a big acknowledgement here.

13) Ernie Banks (.274/.330/.500, 122 OPS+, 512 homers, 2583 hits, 1636 RBI, 64.4 WAR)

The Common Man is totally cheating here, since Banks actually played just over 100 games more at 1B in his career. But, come on, Ernie Banks is a shortstop.

Banks is, of course, much beloved as the long-suffering, always-smiling Mr. Cub, who always wanted to be playing baseball. But for much of the offseason between 1962 and 1963, Banks was in the running for another job, Chicago Alderman. Running as a Republican and on a platform of promoting youth activities and reducing juvenile delinquency, Banks was considered “an intelligent, public spirited citizen” and a “promising young leader” by the Chicago Tribune. The Tribune also pointed out “there are many like him in the new and rapidly growing Negro middle class who would like to run for office and are not yet committed to the Democratic party.” Chicago Republicans did not welcome him, ostensibly on the grounds that he was not a member of the 8th Ward GOP group, favoring instead the very white Gerald Gibbons. Banks refused to bow out, saying “Politics is a strange business—they try to strike you out before you get a turn at bat. I am in this and—with or without the support of the Republican 8th ward organization—I intend to win.” It was not to be, as Banks lost to the incumbent in a landslide, by more than 4 to 1.

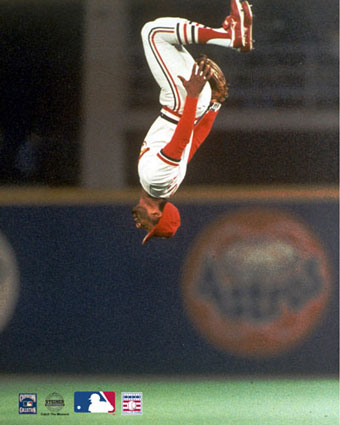

12) Ozzie Smith (.262/.337/.328, 87 OPS+, 2460 hits, 580 stolen bases, 1257 runs, 64.6 WAR)

For what was surely a very short period, Ozzie Smith was the highest paid player in baseball. Ozzie’s contract was set to expire after 1985, and The Wizard was said to be seeking somewhere around $12.5 million over five years and a potential beer distributorship from the Busche family. Negotiations were not going well, and there was a good chance he would be traded during the season (which would have made this moment impossible). Instead, Ozzie budged off his demands, and accepted a four-year deal for more than $2 million per season. His agent told reporters, “In terms of dollars and cents, it makes him the highest paid player. I think the highest contracts are [Mike] Schmidt and [George] Foster at $2 million. Ozzie’s contract…is in excess of $2 million.”

11) Alan Trammell (.285/.3528/.415, 110 OPS+, 2365 hits, 185 homers, 66.9 WAR)

Trammell’s 1984 postseason has to be one of the greatest October performances of all time. In 8 games and 37 plate appearances, hit .351/.500/.806 with a double, a triple, three homers, 9 RBI, 7 runs, and a stolen base. A terrific player for a long time. 20 years. Doesn’t it seem like his career was much shorter?

10) Barry Larkin (.295/.371/.444, 116 OPS+, 2340 hits, 1329 runs, 198 homers, 449 doubles, 379 stolen bases, 68.9 WAR)

It is remarkable that Barry Larkin managed to accumulate so much value, despite playing an average of just 115 games a season. Larkin came up in 1986 with fellow rookie SS Kurt Stillwell. Stillwell had been the 2nd overall pick in the 1982 draft, and advanced steadily through the Reds organization despite not really hitting. Larkin was the 4th overall pick in 1985, debuted in AA and destroyed AAA pitching before earning his promotion. Stillwell hit .229/.309/.258 while Larkin put up a .283/.320/.403. Stillwell actually outhit Larkin in 1987, but the Reds had seen enough to know who the good bet was. They foisted Stillwell on the Royals and got a 23 win season from Danny Jackson for their trouble.

Larkin is generally lauded for remaining a Red for his entire career, but the team did try to deal him during 2000 to the Mets, who were offering Alex Escobar (a huge prospect at the time), and two minor league pitchers. In the end, Larkin refused the deal and stayed with his hometown team because the Mets wouldn’t give him a contract extension. The Reds did, though, giving him $9 million a year over the next three seasons, a move that turned out disastrously for them. The Mets got Mike Bordick instead, who would hit .121 in the postseason to help the Mets lose to the Yankees, and gave up Melvin Mora to do it. Nobody won…except Barry Larkin.

9) Derek Jeter (.314/.385/.452, 119 OPS+, 2926 hits, 1685 runs, 468 doubles, 234 homers, 323 stolen bases, 70.1 WAR)

In 1992, as TCM previously mentioned, the Astros decided not to pick Jeter with the #1 overall pick and he fell to 6th overall. Jeter has a better WAR than every player taken 1-21 in that draft combined. You could actually make a pretty amazing team out of guys drafted 6th overall. Terry Kennedy would catch and John Mayberry would play 1B. Jeter, of course, would take SS, which would allow Gary Sheffield to slide over to 3B. Barry Bonds can handle LF handily, while former teammate and preferred face of the Pirates Andy Van Slyke glides across center. And Kevin McReaynolds can take RF. Zack Greinke would need to pitch every game until Ricky Romero proves himself. There’s no 2B, but Spike Owen could play it in a pinch.

8) Arky Vaughan (.318/.406/.453, 136 OPS+, 75.6 WAR)

Bill James rates Vaughan as the 2nd best SS in history. He’s not wrong, he just values peak performance more than TCM, who’s more interested in career value. At his peak, Vaughan is probably the best offensive SS not referred to as A-Rod or Hans in baseball history.

In 1943, Leo Durocher fined and suspended Bobo Newsom for allegedly yelling at his rookie catcher, but also maybe for ignoring Leo’s advice about how to pitch to particular batters. According to Leo, “I told him it wasn’t far enough inside and he virtually told me I was a liar. Nobody can talk to me like that as long as I’m managing this club.” The rest of the team revolted, and initially refused to play the next day. Vaughan was the only one that held firm, telling him, “Here’s another uniform you can have.”

Durocher, incensed, made the questionable decision to call his entire team and all of the assembled media into the clubhouse for an open meeting. Durocher announced that Vaughan hadn’t been suspended, yelling, “He quit. He turned in his uniform and told me what I could do with it. I didn’t suspend him.” Branch Rickey quickly backed Durocher, and traded Newsom within a week to the Browns (where he balked at going, and suspiciously posted a 1-6 record with a 7.39 ERA before getting sold to Washington, where he promptly recovered). Vaughan’s sit down lasted one game. Despite reports that he and Durocher had buried the hatchet, Vaughan refused to report the next spring, talking about maybe playing the last 2-3 months of the season. Tellingly, he didn’t come back until 1947, when Leo Durocher was suspended for his association with known gamblers.

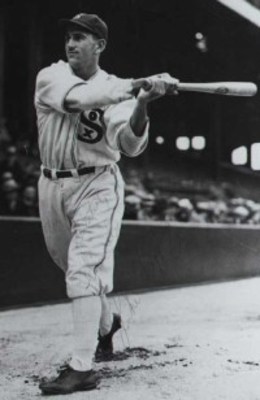

7) Luke Appling (.310/.399/.398, 113 OPS+, 2749 hits, 1319 runs, 69.3 WAR)

For whatever reason, The Common Man loves Luke Appling, the long-serving White Sox shortstop who must have been one of the most aggravating people ever. Pitchers hated him because he could foul balls off seemingly at a whim until he got a pitch he liked. He complained constantly of being hurt. And the White Sox must have had no idea what to do with him once he went into the Army in 1944, and told the AP, “he probably would not return to the major leagues as an active player after the war….He said he already had had trouble with his legs and felt they wouldn’t stand up under a major league season by the time he got out of the army.” Of course, the next year he boasted that “he plans to head straight for Chicago when the discharge ceremonies are completed.” He lasted another six seasons, including one of the greatest ever for a 42 year old in 1949, and told reporters on Opening Day of 1950, “You can’t go on forever in this league, but I’m not through yet.” Jeez, make up your mind already.

7a) Bill Dahlen (.272/.358/.382, 109 OPS+, 2461 hits, 1590 runs, 413 doubles, 548 stolen bases, 75.9 WAR)

7a) Bill Dahlen (.272/.358/.382, 109 OPS+, 2461 hits, 1590 runs, 413 doubles, 548 stolen bases, 75.9 WAR)"He is not at all popular with the fans.... Dahlen, though unsociable and very silent, is an excellent judge of palyers and has made very few mistakes in picking his men. He has made a better showing than any previous handler of the Superbas in recent years and has built up the club into a storng outfit. It is almost certain, however, that he will go at the end of the season and some one else will take the thankless job of trying to manage the Superbas without having any real authority except to say who is going to pitch."

6) Robin Yount (.285/.342/.430, 115 OPS+, 3142 hits, 1632 runs, 1406 RBI, 583 doubles, 126 triples, 251 homers, 271 stolen bases, 76.9 WAR)

Most of the kids out there know that Yount moved off of shortstop midcareer to become a centerfielder. This has been used in the past to justify, say, calls for Derek Jeter to abandon the position. But rather than a lack of range, brought on by age, Yount had developed shoulder trouble in 1984 and the Brewers were worried about his ability to make the throw to 1B. Normally, you’d put a SS who can’t throw somewhere to minimize the strain on their arm. 2B maybe. Or 1B if they can hit a little. Those positions were taken, though, by Jim Gantner and Cecil Cooper respectively. 3B was locked down by fellow HOFer Paul Molitor. So the Brewers moved their superstar out to left field at the start of 1985. The results were promising,

“The life-long shortstop has taken to left field as if he had been playing there for a lifetime, or at least a career. Yount, who will be in left until his surgically repaired shoulder is ready to make the throw from shortstop, is running down fly balls with ease, cutting off balls headed for the gap and playing the wall as if he had a built in radar.”The article goes out of its way to proclaim that this is a temporary situation, and that Yount would be back at short as soon as his arm could handle it. But Yount’s shoulder never really got better. He had more surgery that September, and the Brewers were pleased by the play of Earnest Riles, so they tentatively penciled him in for center field and the rest is history.

There are four players named Robin who have played in the Major Leagues. Two of them (Yount and Roberts) are in the Hall of Fame. Another (Ventura) was a terrific 3B for a long time and a borderline candidate. The other one is a journeyman named Robin Jennings. That’s weird, right? And good odds. If TCM and The Uncommon Wife have another kid, we’re naming him or her Robin. Couldn’t hurt.

5) Pee Wee Reese (.269/.366/.377, 98 OPS+, 66.7 WAR)

Reese gets mentioned in the same breath as Phil Rizzuto so much it’s hard to remember that Reese was actually a much, much, much better player. The two players were in the league together for 13 years. Reese was a better player in 10 of those years, finishing behind Rizzuto only in 1941 and 1950, and essentially tied with him in 1952. Reese had a lower batting average, but a higher OBP, SLG, stole more bases, and was productive for an extra year that Rizzuto wasn’t in the majors. Reese also missed three years for World War II. Reese was incredibly bitter about not being in the Hall of Fame until his induction in 1984, refusing even to attend his teammates’ inductions. He was right to be pissed and all, but that’s pretty cold.

4) Cal Ripken Jr. (.276/.340/.447, 112 OPS+, 3184 hits, 1647 runs, 1695 RBI, 603 doubles, 431 homers, 89.9 WAR)

Only two blemishes on Cal’s career:

One, he is the all time Major League leader (since they started keeping track in the 1930s) in grounding into double plays. Of course, to get to that point, he had to be great enough to stick around that long. Which he was. And he had to not be very fast or quick. Which he wasn’t. Despite his lack of quickness and speed there’s no denying that Cal played a terrific shortstop, allegedly because no one was as good at positioning themselves before the pitch as he was.

Two, it’s possible he may have hurt his team by refusing to take a day off every now and then:

| Month | AVG | OBP | SLG |

|---|---|---|---|

| Apr/Mar | .274 | .344 | .446 |

| May | .263 | .340 | .453 |

| June | .294 | .352 | .460 |

| July | .286 | .354 | .466 |

| Aug | .275 | .333 | .433 |

| Sept/Oct | .262 | .320 | .428 |

Here are Cal’s rate stats by month: Obviously, by the end of the season, he was wearing down. In September, when he should have been facing inferior pitching, he had his worst months. The O’s lost the AL East in 1982 by a single game, but Cal hit .252/.333/.504 in September/October, so that didn’t hurt them. In ’83 they won it all, but then didn’t compete again until 1989. That year they finished 2 games out, and Cal hit .198/.284/.356 after September 1st. In 1992, the O’s finished 7 out, and while Ripken wasn’t responsible for all of that, his .222/.286/.301 line from July 1 onward didn’t help either. Is it any coincidence that his last two great seasons, 1994 and 1995, came when in shortened years? What he accomplished, on its surface, was wonderful. And The Common Man has no doubt that Cal did it with (mostly) the best of intentions. He was, after all, the best shortstop on the team, and maybe in the American League. But by not taking a day off now and then, did Cal cost his team games and a chance at the postseason when they needed him most? Is it blasphemous to say “maybe?”

3) George Davis (.295/.362/.405, 121 OPS+, 2665 hits, 1545 runs, 1440 RBI, 453 doubles, 619 stolen bases, 90.7 WAR)

Bill James has a terrific trip through Davis’s career in his New Historical Abstract that includes him rescuing women and children from a burning building, and a nice synopsis of what it was like working for a world class nitwit like Andrew Freedman, “Monte Ward quit as Giant manager as soon as he heard that Freedman was buying the team, leaving baseball to practice law…. Davis managed the Giants for 33 games and then quit in disgust…. Freedman would negotiate salaries with the players, and then reduce the salaries by fining the players hundreds of dollars for petty or unspecified offenses. In one game Freedman, wandering on the field to abuse the umpire, found himself encircled by angry fans.” Davis was inducted into the Hall with very little fanfare. Baseball had organized an effort to get a couple of additional 19th century players in the Hall during the late 1990s, and settled on Davis in 1998 and McPhee in 2000. There wasn’t much of a push to get anyone else in, as their lobbies have, understandably, diminished in voice over the last few decades.

2) Alex Rodriguez (.303/.387/.571, 2672 hits, 1757 runs, 1831 RBI, 474 doubles, 613 homers, 301 stolen bases, 101.9 WAR)

This is neither an endorsement of, nor an indictment of Alex Rodriguez…simply the truth. A-Rod may have been the single most gifted player ever to play the left side of the infield. Look at those numbers above and realize that he’s done all that before he turned 34. More than any other player, Alex Rodriguez had no need to seek out performance enhancers. But he did. And now we’re stuck with him. It’s likely that A-Rod won’t be on this list much longer. Three more years at the hot corner, and he’ll have played more games there than at SS.

1) Honus Wagner (.328/.391/.467, 150 OPS+, 3420 hits, 1739 runs, 1733 RBI, 643 doubles, 252 triples, 101 homers, 723 stolen bases, 134.5 WAR)

It’s almost less interesting to talk about the dominant guys, as you know a lot about them already and, frankly, The Common Man runs out of superlatives after a while. But if any player, other than Ruth, deserves all the compliments you can think of, it’s Wagner. In a fawning article from 1908, Pittsburgh Press columnist Gertrude Gordon runs through the normal platitudes about Wagner’s decency and humility, and fitness as an idol of youngsters, and tells of how Wagner isn’t willing to give her a traditional interview that day. But, she says,

“Without any thought of it, and with not the slightest effort, he teaches a lesson of contentment that it might be well to learn and learn well. The simple kindliness of his nature is evidenced in the way that every dog and child of the neighborhood fairly worships him, and that he never is too hurried to say at least a word of greeting to them. He fits perfectly into a place where nine men out of ten would be utterly spoiled. He gives the impression of meaning just what he says, and more, of saying just what he means.

When on my leaving he gave me a crushing hand clasp and said ‘Come back next spring and I will talk to you,’ I was glad, for I want to go back and see the automobile again, and the chickens and the dogs and horses, and that gentle courteous gentleman, Honus Wagner.”

45 comments:

I tried ranking all time shortstops in relation to Jeter a year and a half ago:

http://www.bensbaseballbias.com/2009/08/short-stop-for-shortstops.html

It's admittedly not a great piece but I still find it interesting that Jeter, despite all his overrated-ness, could make a case as the 2nd best SS ever when he's done.

Um, Mark Belanger and Zorro Versailles?

Belanger was relatively close to making the list. Of course, he's one of the greatest fielders in baseball history, putting up almost 21 wins above replacement over, roughly, 14 full seasons. But his offense simply was not good enough to merit inclusion.

Versalles had an incredibly short career (essentially 10 full seasons). He was a great player for exactly one season and a good player for only 5 others before injuries robbed him of his effectiveness. At just 11 Wins Above Replacement, he is not even in the discussion.

No mention that Jeter was, by common agreement, never more than average defensively, and has often been terrible?

Well, a certain subset of awards voters disagree with you. But yes, indeed, Jeter has been an occasionally competent but mostly bad shortstop in his career.

But is that news to anyone at this point though? Is it necessary? Part of the fun of lists like this is that we don't have to rehash the same critiques and criticisms over and over. Yes, he is a bad fielder, but he's also been a terrific overall player.

Dave Concepcion? I think that he should be someplace among 30 and 40 greatest SS ever.

Yeah, Concepcion is easily the most glaring omission. Clearly the best SS of his generation (emphasis on SS - unlike quite a few on this list who had to change positions for a decent portion of their careers). Concepcion probably belongs in the Top 10; top 15 max.

Jay Bell and Ed McKeon make the list, but no Marty Marion? Hmpf! Thanks for recognizing Bobby Wallace, at least.

IIRC, Vaughan always claimed that he did not take those years off because of the Lip, but rather because his father (or perhaps father in law) died and he had to go home and take care of the family farm.

Not a reason for retiring one heres much anymore.

Definetly Dave Concepción was missing on the list! Prolly the best SS of the 70's decade.

Re: Concepcion At 33.6 WAR, Concepcion is just on the outside looking in. If TCM were to discount players for their time at other positions, Jay Bell and Rico Petrocelli would fall off the list, leaving room for Davey. However, he definitely benefits from a halo effect thanks to great teammates like Morgan, Bench, and Perez, who truly made The Big Red Machine go and who continue to bang the drum for how great he was. The truth is that Davey was an incredibly inconsistent player whose effectiveness was almost always tied to the randomness of batting average on balls in play. He had 10 seasons ranging from good to very good, but also had a lot of years where he was at or below replacement level. At the peak of his game, he belongs in the top 30 SS all time, probably. But taken as a whole, his career is far less impressive. Bert Campaneris, with whom he was often linked, was much better.

re: Arky Vaughan

Vaughan certainly did deny that his absence had anything to do with Durocher. That said, this was a huge incident for the Dodgers and it's certainly suspicious that Vaughan refused to return until after Durocher was gone from the team.

@ Bill K.

Slats had an incredibly short career that was basically over by the time he was 32. At his peak (say when he won the NL MVP in 1944) he was one of the greatest defensive shortstops in baseball history. But he didn't play long enough, nor hit enough, to accumulate enough value to be included here.

No mention of Edgar Renteria? He might fall short by some counting totals but he did have a fantastic peak.

I guess I am a little surprised Jimmy Rollins hasn't made the cut yet. Over Jay Bell at least. He is an MVP and has some decent counted stats thus far. Plus a WS ring. Any thoughts?

Re: Renteria and Rollins

Both are very close, needing one more solid season each. Rollins is far more likely to make it, obviously, with Renteria slowing significantly and beginning to contemplate retirement. Rollins does, however, need to reverse his recent trend of bad, injury plagued years.

I found a a few references to Cronin's knee technique:

http://books.google.com/books?id=NS4DAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA41&dq=joe+cronin+knee&hl=en&ei=cLYCTfHRL4H88AbS-9TnAg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=2&ved=0CCwQ6AEwAQ#v=onepage&q=joe%20cronin%20knee&f=false

http://books.google.com/books?id=Pu_l-QMmJtMC&pg=PA123&dq=joe+cronin+knee&hl=en&ei=cLYCTfHRL4H88AbS-9TnAg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=8&ved=0CEoQ6AEwBw#v=onepage&q=joe%20cronin%20knee&f=false

http://books.google.com/books?id=yDMDAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA80&dq=joe+cronin+knee&hl=en&ei=cLYCTfHRL4H88AbS-9TnAg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=10&ved=0CFUQ6AEwCQ#v=onepage&q=joe%20cronin%20knee&f=false (the same incident as the first link)

Excellent, thanks Harry! The Commmon Man will have to start double checking Google Books.

Yeah, the more-or-less complete run of Baseball Digest is reason enough. I've spent hours reading old issues. Terrific finds on the old articles, BTW.

I don't agree with your comments on Vizquel. I don't know if he should be in the Hall of Fame, but his OPS+ is as good as those of Smith and Aparicio, was better than Ripken in RF/9 when they were both active, and was a leading short stop from 1990 to 2009 according to TZ, RF/9, UZR, and The Fielding Bible. He won't be the worst short stop to enter the Hall of Fame if that happens

Is this a list of greatest players who played shortstop, or a list of greatest shortstops? i.e. Ozzie Smith was a better shortstop that A-ROD, but A-ROD was a better player.

What a strange question. What's the difference? It very likely that Ozzie Smith is, by far, the best defensive shortstop to ever hold down the position for any length of time. But isn't half of a shortstop's job to hit the baseball?

Or do you objecting to the rankings of players like Banks, Ripken, and Yount, who were forced to move off the position? In which case, The Common Man would say that he is defining a shortstop, as he mentions above, as someone who played either the majority of his games at the position, or more games there than he did elsewhere. However, again as TCM points out above, he makes an exception for Banks.

Reese seems at least 5 spots too high.

Based on his raw numbers, The Common Man can see how you might think that. We, as baseball fans, have done a good job of forgetting how excellent he was.

Both WAR variations have him in worth in excess of 66 wins over his career, he never really had to come off of the position, had a terrific eye, and was a very good fielder. When you account for that and the fact that he missed three full years for WWII, The Common Man is confident in his placement within the top 5.

Is there any reason why you didnt use fangraphs WAR?

Here is their version of the greatest Shortstops ever via their version of WAR: http://www.fangraphs.com/careerleaders.aspx?pos=ss&stats=bat&type=6&min=500

Ozzie Smith was the greatest defensive Shortstop of all time and Shortstop is regarded as the most important defensive position on the field. That fact alone makes him a top 5 all time and perhaps even the best all time. Its sort of an insult to have him so far back from the top spot on your list.

@PL

The Common Man used BR.com's version over Fangraphs' partly because he's more comfortable with the interface and mostly because TCM is slightly unclear about how Fangraphs calculates WAR differently for players who played before Total Zone Rating (on which they base their WAR for contemporary players). If they are using different criteria to judge, say, Jeter and Wagner's defense, how can we trust the accuracy of the ratings? BR.com, to my knowledge, uses the same stats with everybody.

@ anon

That's, frankly, a ridiculous statement. Mark McGwire was the best homerun hitter in the history of the game. Does that make him the best hitter? Of course not, because we're talking about value, which in this case can be quantified, not skill in one particular aspect of the game. Overall, Ozzie was terrific, and probably the best fielding SS who ever got a chance to play regularly in the majors?

Should he feel insulted that TCM ranked him 12th all time? Well, 7,921 players have played more than 100 games at SS in baseball history and TCM says that, overall, Ozzie was the 12th best ever. If you worked in a field where there were 8,000 other guys who did the exact same thing you did, and TCM said you were in the top 12, would you be insulted? That's ridiculous and idiotic.

Well, when you say the word shortstop, I don't think of Alex Rodriguez. The word "shortstop" doesn't define him. Its more like power hitter, or perhaps great hitter that comes to mind first, not the word shortstop. He just played shortstop. But when you say the name Ozzie Smith, you think of a shortstop. I think, to make this list legitimate, we have to transcend the numbers (WAR included) and think of what a great shortstop really is. You know one when you see one. While you rank AROD very high because he hits very well, he's not a great fielding shortstop. So, in a sense, his greatness doesn't come from being a (former) shortstop, but from his hitting.

In short, please use more intangible ways to measure shortstop greatness, not just numbers. Don't just use your brain, but whats in your heart. When you think of AROD, do you really think of the words "great shortstop"?

Your thought processes are baffling.

Did Alex Rodriguez play SS more than any other position? Yes. Then he's a SS as defined by this list. So too, is Ozzie.

But all of us, whether we play baseball or not, play multiple roles. Shortstop, leadoff hitter, Detroit Tiger, team leader, etc. Guys inhabit more than one role. TCM is a husband, father, writer, working man, baseball fan and more. None of these things define him absolutely. When TCM makes a list of the greatest hitters of all time, you can be sure that some of these players will make a return to that list as well. Because guys don't just fit into the tiny pigeon hole in which you seem to be trying to put them.

When you think of AROD, do you really think of the words "great shortstop"?

I do. I don't know why you wouldn't. That's what he was.

Look, when they change the rules and everyone gets a designated hitter for their shortstop, then what PL is saying will have merit. But for now, hitting is half of what a shortstop has to do, and it's silly to define "great shortstops" only by one half or the other. It's not like A-Rod was a first baseman they stuck at shortstop, either; he won two Gold Gloves out there, and probably deserved one or two more. When you put together all those things a shortstop has to do -- hitting, running, and fielding -- it's pretty clear that A-Rod was a better one than Ozzie. The numbers back that up, but my "heart" tells me that, too.

So when AROD retires, and you see him on the street, are you going to say, "Wow, there's AROD, one of the greatest shortstops to ever play the game"??? Hell no.

First of all, A-Rod isn't likely to live anywhere near me. Nor is he likely to be randomly walking the street when he can be carried by his litter of manservants. But if The Common Man were to catch a glimpse of him in his golden throne as it passed by, he'd say "there goes A-Rod, one of the greatest baseball players that ever lived. If he had stayed at the position he may have been considered the greatest SS ever."

This is so ridiculous. How in the name of all the swears TCM wants to scream at you right now are you this thick?

Look, Cal Ripken played SS but didn't look like a SS. And he's probably defined by his streak more than his position. Should we therefore ignore the fact that he was one of the greatest SS ever, and simply call him the most durable man who ever did live?

No, because again, he is more than that. He's the greatest Oriole in history, for one thing. He's also the greatest member of the Ripken siblings. And he's the greatest bald guy to play in the big leagues. There's something. How you think of him first depends entirely on your perspective and what you value. So to TCM, he thinks a player's overall contributions matter more than TCM's subjective judgments of him as a player. TCM's not likely to come off that position just because you stupidly define a SS in a limited way and would like TCM to do so.

Bill said "hitting, running, and fielding"...

Seems like Ozzie was a better fielder, and he has almost twice as many stolen bases as ARod...so Ozzie has two out of three?

Oh my God, what a beautiful, magical fairy land you must live in where your opinion is all that matters and it doesn't have to be supported by "evidence" and "solid reasoning" in order to matter and convince others of your absolute brilliance. TCM wants to go there, for he will soon be king of the idiot people.

Just because Bill said "hitting, running, and fielding" doesn't mean that all three are valued equally. Indeed, baserunning is a far less important part of the game than either hitting (where A-Rod not only dwarfes Ozzie, but laps him 2-3 times) and fielding (which, while important, is not nearly as important as you think it is. Also, A-Rod was a hell of a SS for the time he was on the position. As Bill points out, he won a couple Gold Gloves and deserved to win more.

Its your list, common man...

TCM, you state at the outset that you're valuing career value over peak value, but it would be interesting to do it the opposite way (especially since SS is a position that even the greats are invariably moved away after their peak years).

Ernoe Banks, for example had years of 9.7 WAR and 10.0 WAR...at his peak, he was more valuable than almost any SS in history. The only 10+ SS WAR years in history are by Honus, A-Rod, Yount, Ripken and (oddly) Loue Boudreau.

I'm confused by the inclusion of Pee Wee Reese in the top 10 when none of his stats seem to support it. I am also confused by the equation of deadball players with players who have played in the integrated era. It's your list, so you can make up the criteria how you choose, but, in my opinion, it just doesn't make sense. Anyway, I like the debate you've started, even though I disagree with you mightily.

@ Anthony

re: Pee Wee Reese, the reason you don't see it is a function of his WWII service. Reese had a WAR of 6.2 in 1942 and 5.9 when he returned in 1946, so TCM, conservatively, gave him credit for about 15 WAR for the time he missed. With three more years, he'd be above 2600 hits, and his rate stats would have improved with more seasons during his prime to counterbalance a couple weak ones at the end. Also, don't discount his patience, which truly made him a weapon in that Dodger lineup.

Re: the inclusion of different eras. We have tools to allow us to compare players from different eras on a level playing field. What's your question?

@ Anon

While TCM's sure that looking solely at individual seasons would be interesting (though one excellent season doesn't make for what we would typically define as a player's "peak"), TCM would object strongly to consider this as a criteria for "greatness." For any list that John Valentin appears on is, by definition, not a list that tells us anything about "greatness."

It looks like, for the most part, you just rank the all time short stops by WAR. Anyone can do that, how original.

Your sarcasm is duly noted.

That said, here's what TCM wrote in response to similar criticisms at Baseball Think Factory:

"I want to address a couple of the criticisms here. Yes, I did largely use a "straight WAR" criteria for coming up with this list, with the exception that I gave players who served during WWI, WWII, the Korean War, or Vietnam additional credit for their time missed. I believe, as Bill points up above, that we should not discount the contributions of a player after they leave the position, particularly since there are some SS who are never able (or never willing) to move off of it and those players utterly stop accumulating value for their teams (like Marty Marion, for example). I don't think it's right to essentially give them an advantage simply because their careers got cut short.

Also, I can see additional value to going off of a mean of WAR methodologies, and in adding peak value into the discussion. The problem I run across, particularly in relation to the "peak value" question, is how much of a weight to give it. I would like my lists to be filled with as little subjective assessment as possible once I choose the criteria on which players will be looked at. And so the discussion of whether Arky Vaughan deserves some extra credit for his short career compared to, say, Luis Aparicio, and how much extra credit to give him, I believe, discounts the fact that Aparicio continued to provide excellent value to his teams into his late 30s. I find that overall value particularly impressive, and pretty damn "great."

I know the ultimate takeaway from lists like these is where certain players rank. And who's included and who's not. But more than anything else, what I value most about these lists is the opportunity to tell stories about players that a lot of baseball fans haven't heard. Like that Wally Pipp probably didn't actually have a headache. Or that Ernie Banks ran for Chicago Alderman and got creamed. I think these add a lot of value to the task of listing itself. Because just a list of players isn't all that much fun to look at, and it's in contextualizing these players and their careers that I have the most fun (and spend the most time)."

I love these debates, so please allow me to add my own thoughts:

1.) If we are truly going to judge the greatest SS based soley (or mostly) on WAR, then shouldn't we isolate WAR to just games at SS? I presume this would enhance (relative to this exercise) players such as Ozzie, Jeter (both EXCLUSIVELY played SS), and Larkin (only 3 games not at SS, his rookie year), while at the same time deducting from Cal, Arod, Yount, and others who were, for one reason or the other, forced to move from the SS position as their careers progressed.

2.) If we are going to base our evaluation soley on accumulated statistics, then we CAN NOT assume for any missed part of their career due to war or any other measure. As soon as we start to 'assume' what someone WOULD have done, we've opened the subjective pandora's box that would seem to chip away at the foundation of your very exercise.

Im a huge 'intangibles' guy, but intangibles are subjective and counter-productive for an exercise using stictly compiled statisitcs. For this very reason, assumption of what someome WOULD or COULD or PROBABLY would have done goes against the very grain of this particular analysis.

3.) On the other hand, my favorite exercise is actually building my own team from the historical pool of players. This greatly changes the dynamic of any 'greatest list', but I feel it's important, because after all, there's still a game to be played, AND, as much as qualitative and quantitative stats can give a pretty good idea of a players long term value, it does not neccesarily take into account every single nuance, of every single play...many nuances that cannot be COMPLETELY accuratley measured by the current measure of statistical data.

So what does this mean? While it might be accurate to say that Ozzie Smith is the 12th greatest SS by your process (and considering that this pool contains HOFers that spent many years at other positions, that's an even more appreciable accomplishment), I personally would want Ozzie as my SS (exluding Wagner, who played several postitions and is simply one the elite-of-the-elite players regardless of position), for the reason that, if you belive Ozzie was the greatest defensive SS, and SS is the most important (arguable vs. catcher) defensive postion, then I can get all the offense I need from 1B, OF, etc...and it's not as if Ozzie wasn't a useful offensive player after his first few seasons (which of course, factors into the overall career value, and rightly so, for your exercise).

Anyway, thanks for taking the time to make your list and continuing the long-held tradition of baesball debate.

@anon...It's irrelevant that shortstops is the most important defensive position because all of the guys he is being compared to here were also shortstops.

Albert Pujols, not Cal Ripken, has been the greatest bald player.

Post a Comment